Context

“This drought has been devastating. It was one season after another of failed rains. Since the beginning, the way people have lost their livestock, it’s been complete decimation. The drought left some households completely destitute, so they had to move into urban areas to seek humanitarian support.”

Since the rains failed in 2021, Somalia’s rivers and wells have dried up, more than 3 million livestock have died, and harvests all over the country have repeatedly failed.

As a result of this crisis and other challenges, such as rising inter-clan violence and an intensive campaign against an insurgency, people have fled from their rural homes to urban centres in record-breaking numbers. There are now an estimated 2,400 internally displaced persons (IDP) camps hosting over 1.5 million people in Somalia. A lack of adequate shelter, over-crowded conditions, and limited access to basic services such as water and healthcare make those who have fled one of the most vulnerable groups in the ongoing crisis.

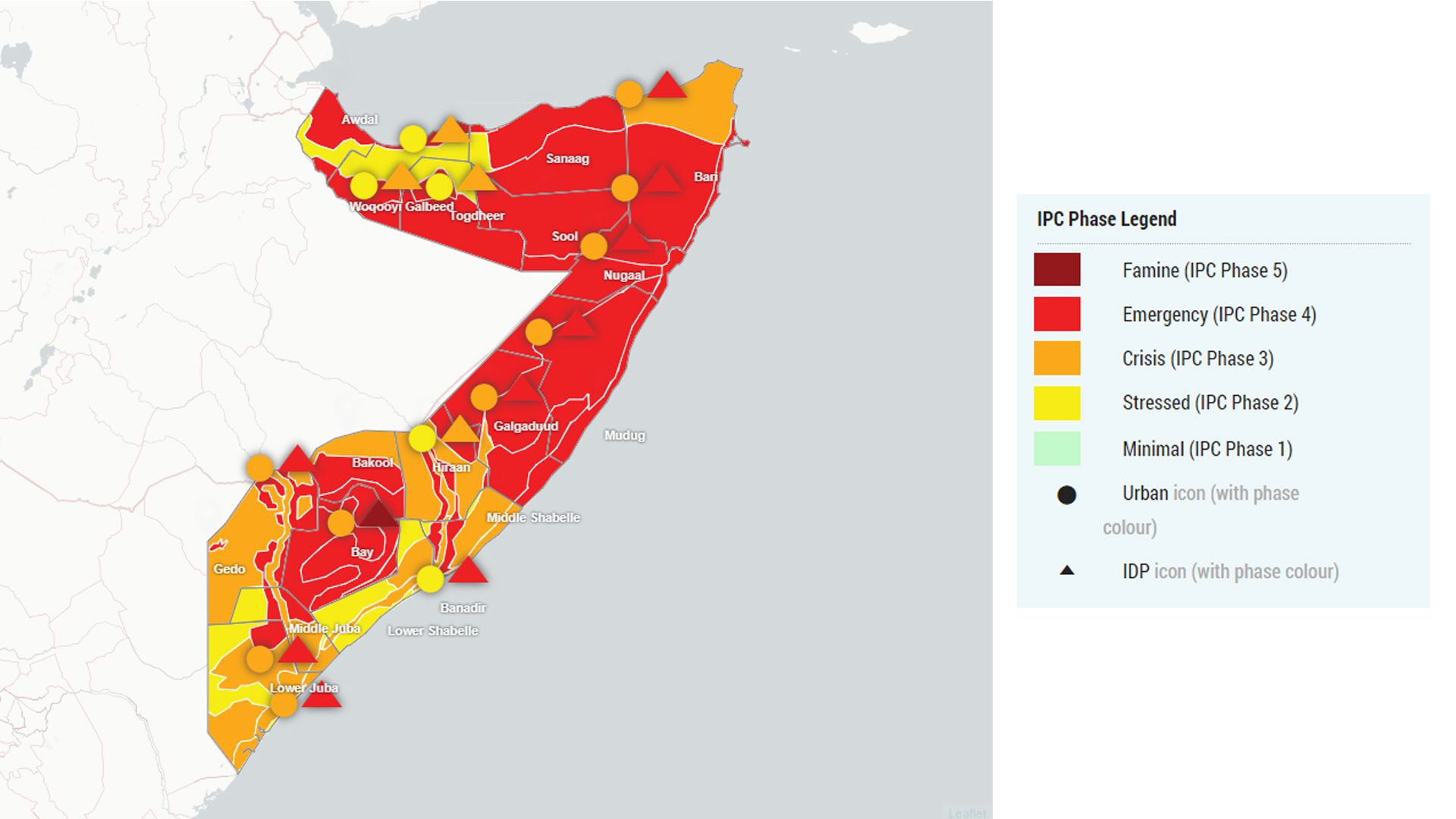

Five seasons of failed rainy seasons created famine-like conditions, leaving 5 million people in acute food insecurity, placing more than 2 million children at risk of malnutrition, and causing the deaths of as many as 43,000 people in 2022 alone.

IPC Map from October-December 2022 at the height of the crisis. Click here for the interactive data.

IPC Map from October-December 2022 at the height of the crisis. Click here for the interactive data.

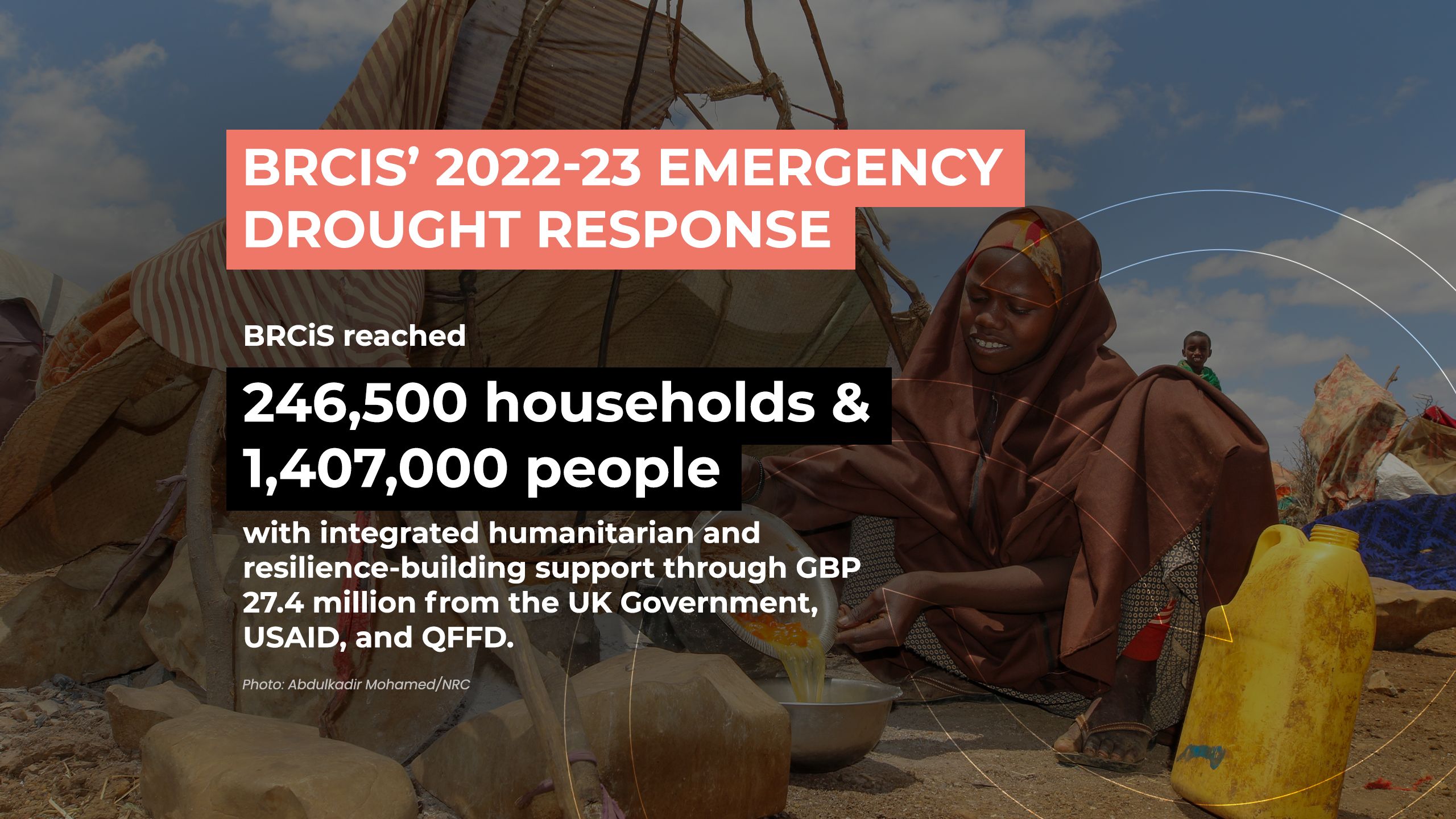

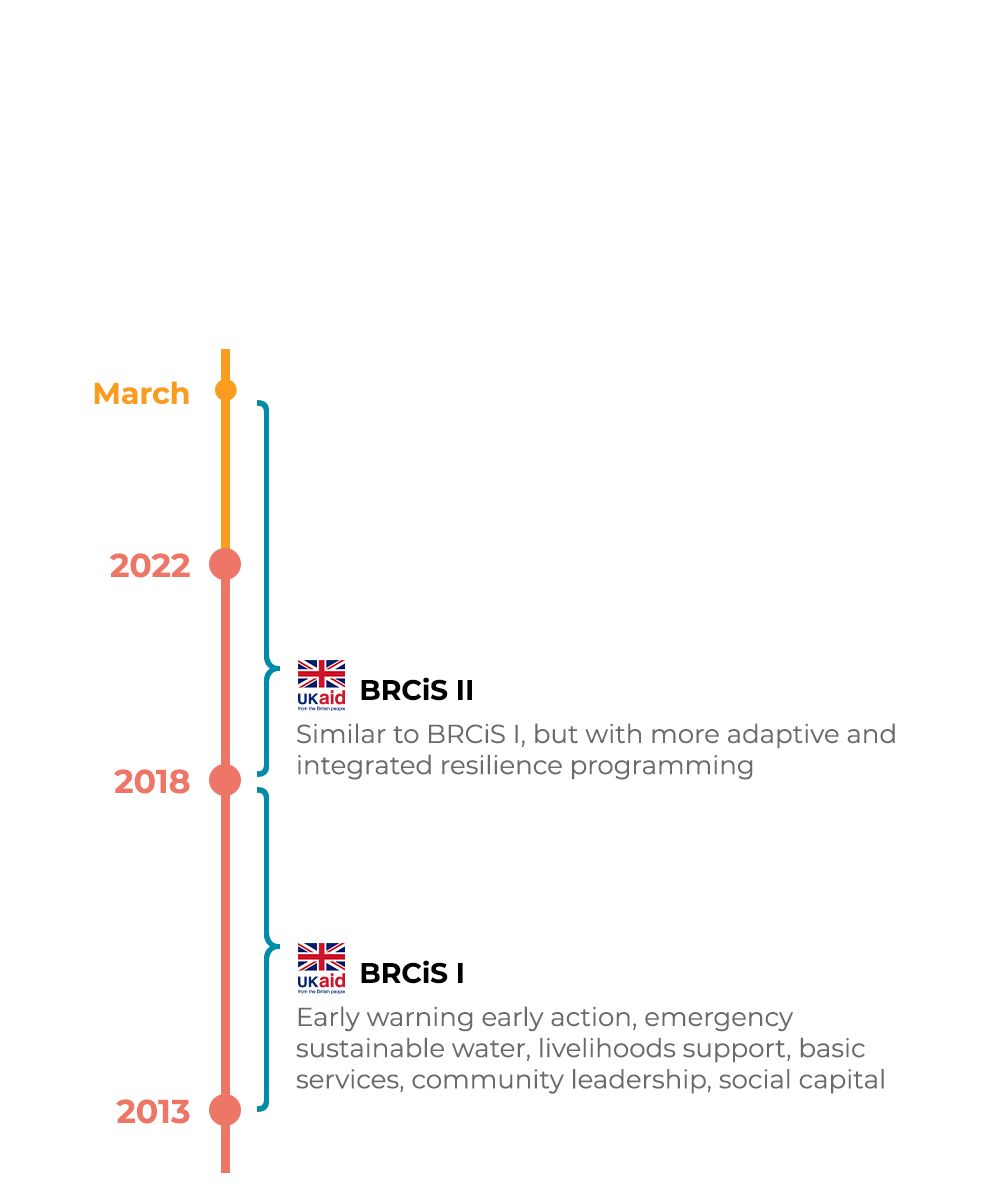

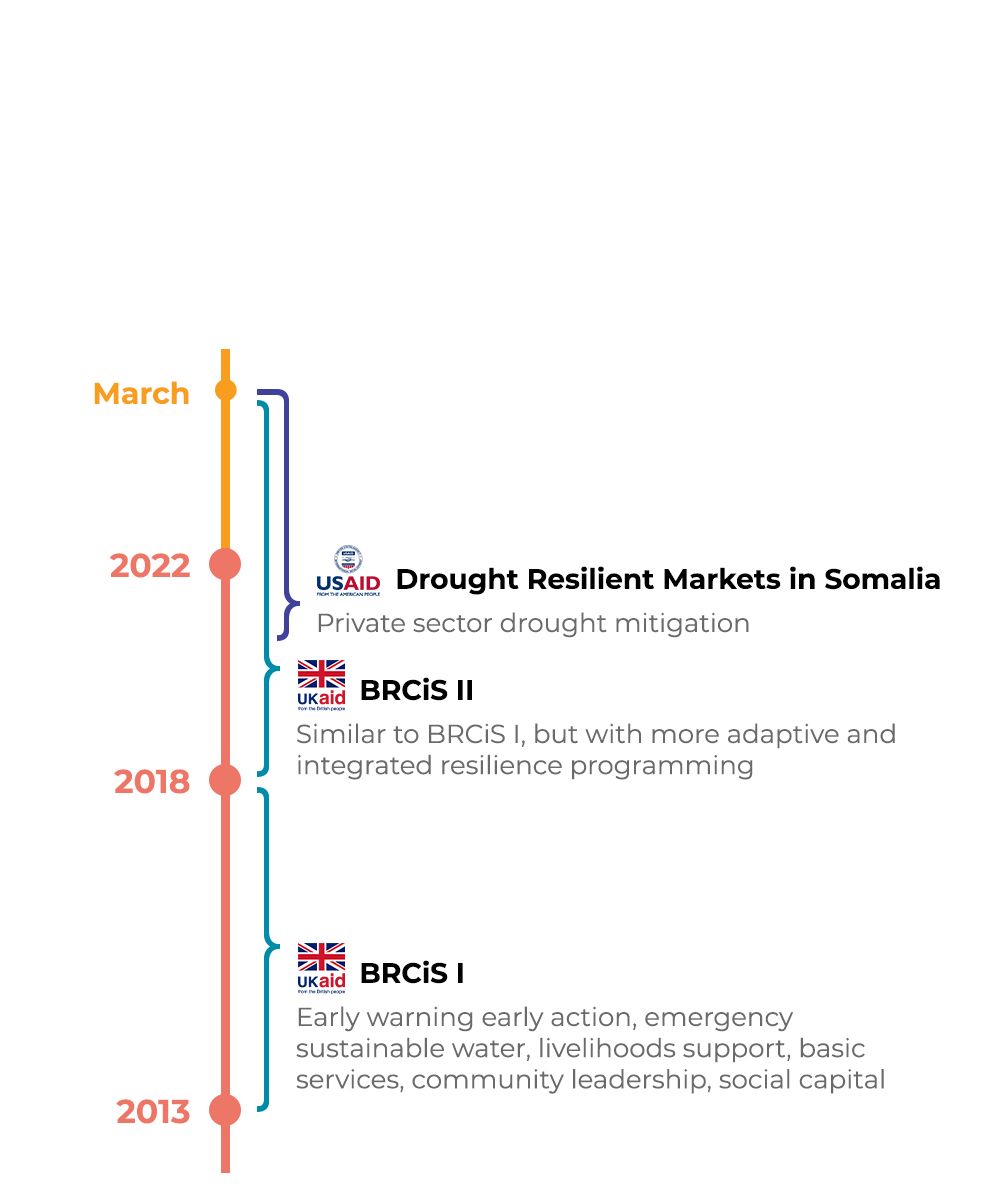

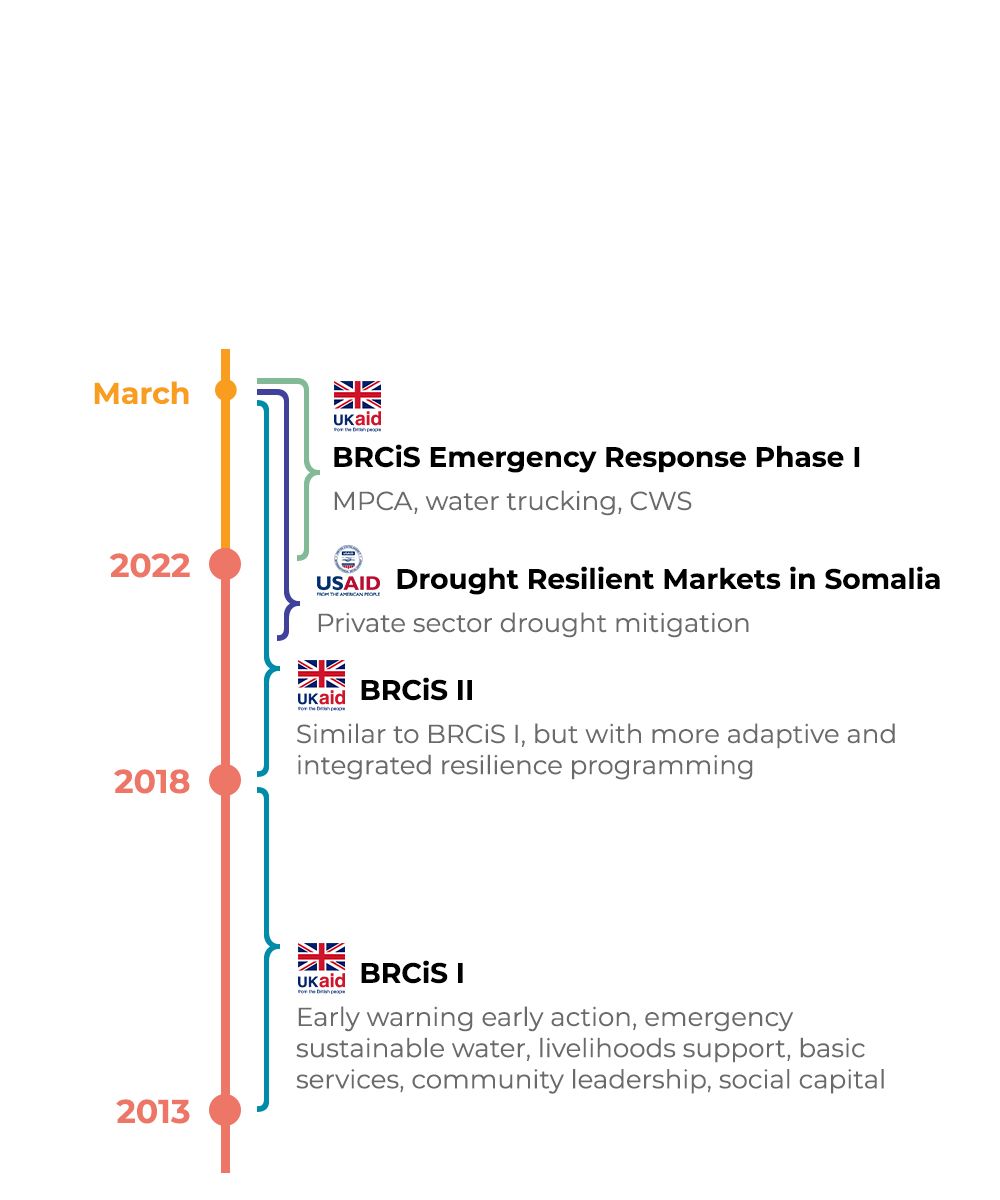

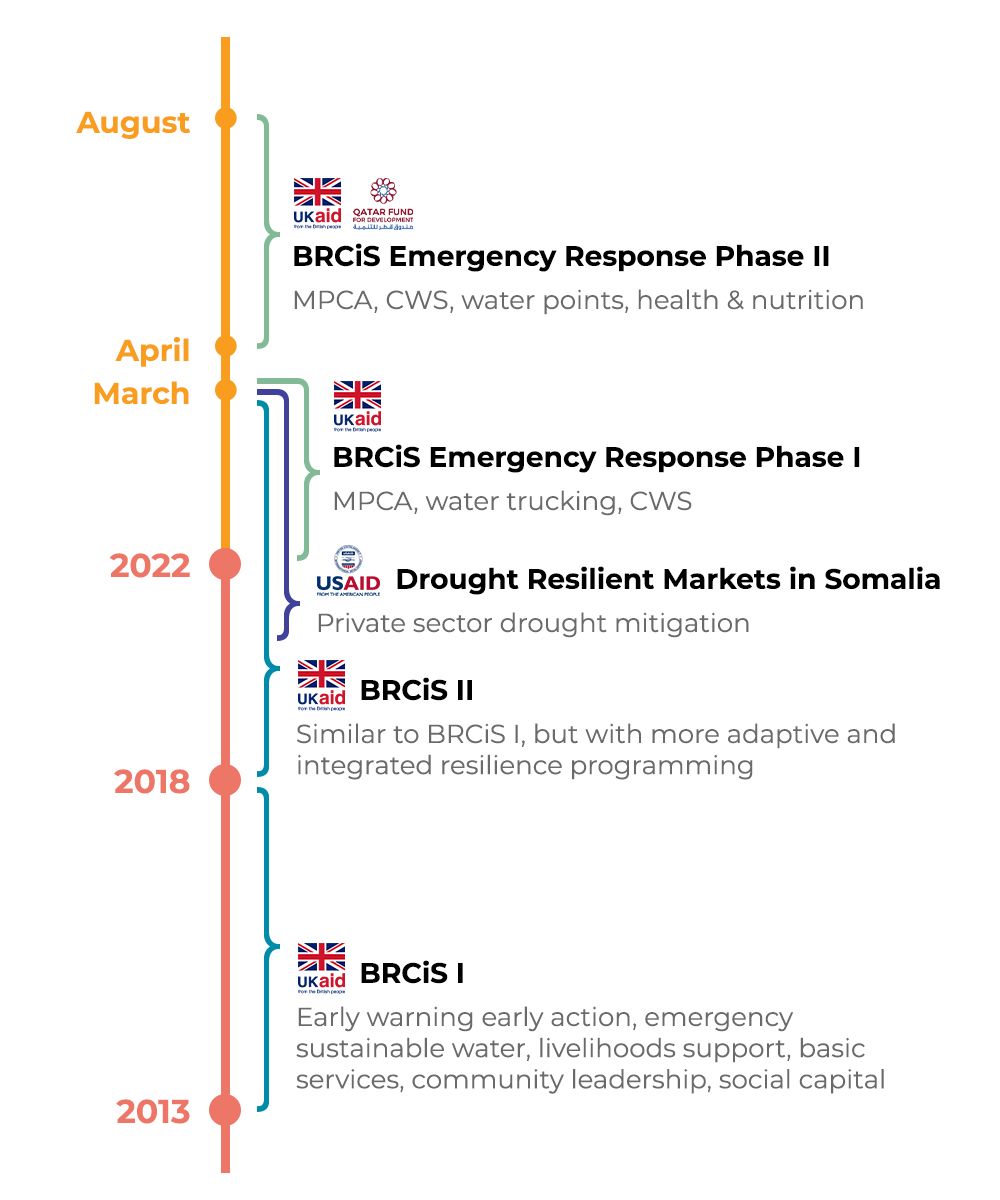

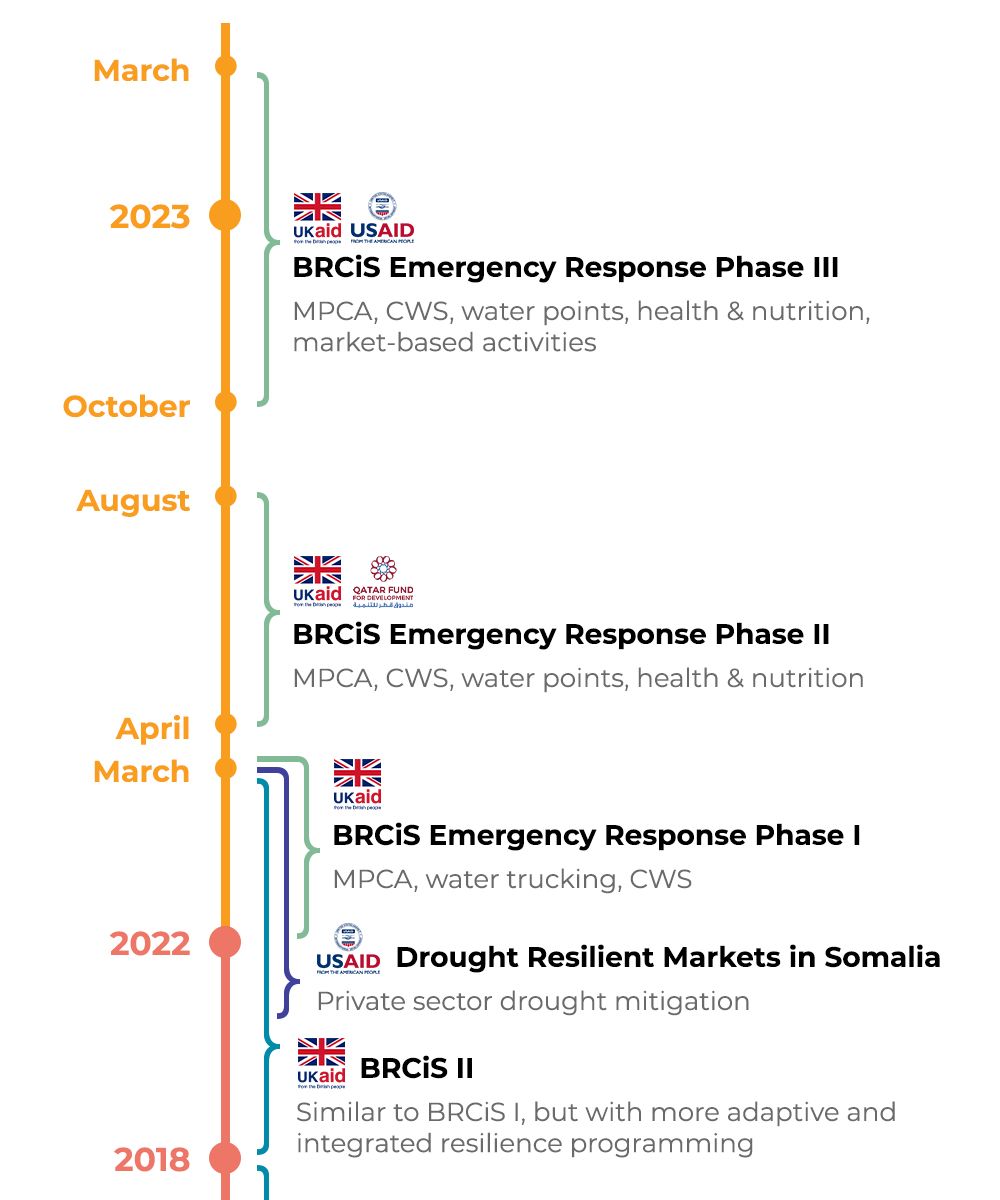

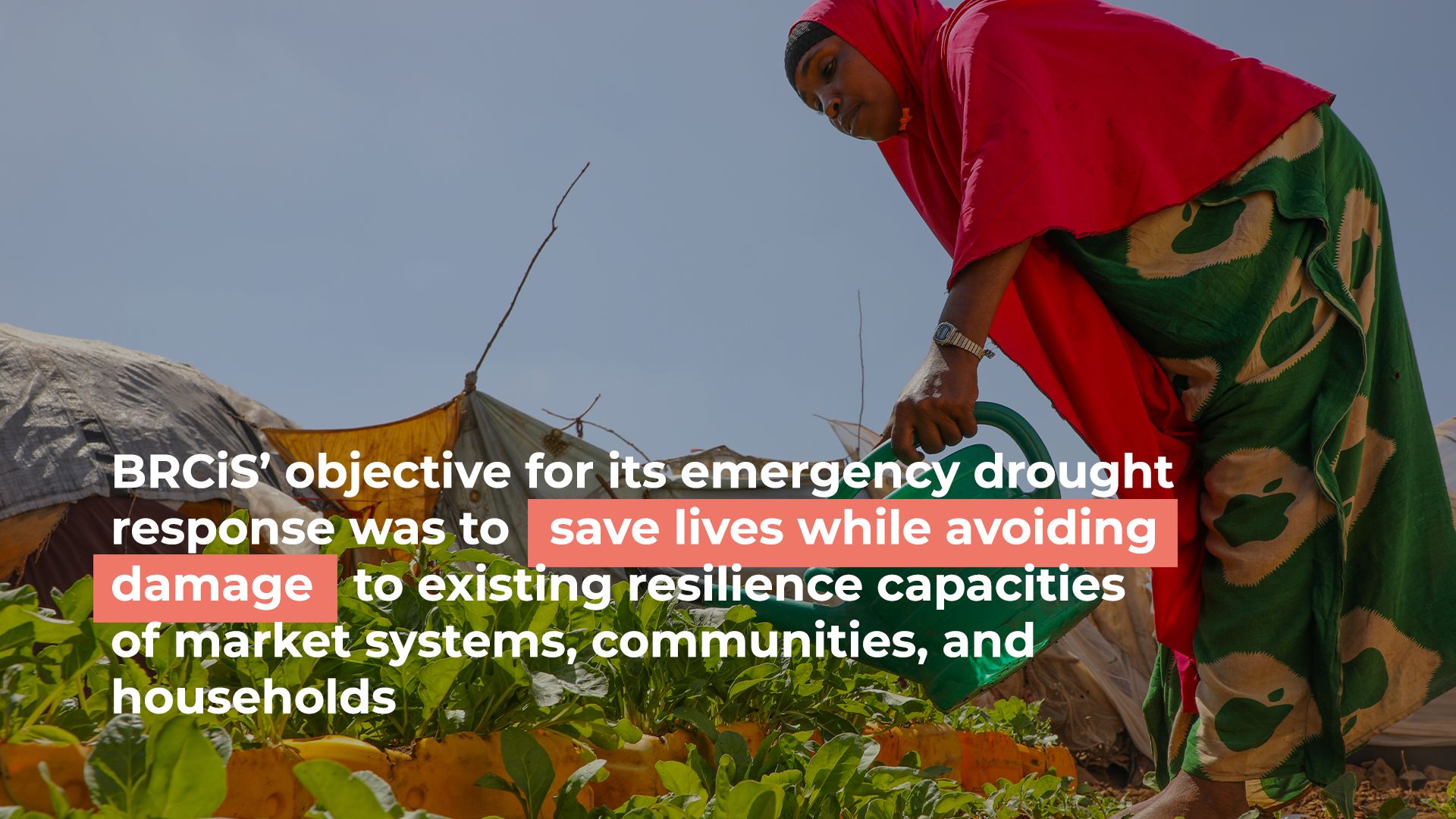

Having worked closely with rural communities to build resilience and mitigate the potential consequences of shocks in Somalia’s crisis-prone context since 2013, the Building Resilient Communities in Somalia (BRCiS) Consortium was monitoring the drought situation as it emerged in 2021 via its Real-Time Risk Monitoring System. Since part of the BRCiS II mandate was to conduct early action and emergency response activities when disaster strikes, the Consortium began to scale up its activities. As conditions worsened, both USAID and the UK Government stepped in with short-term supplements to support this effort.

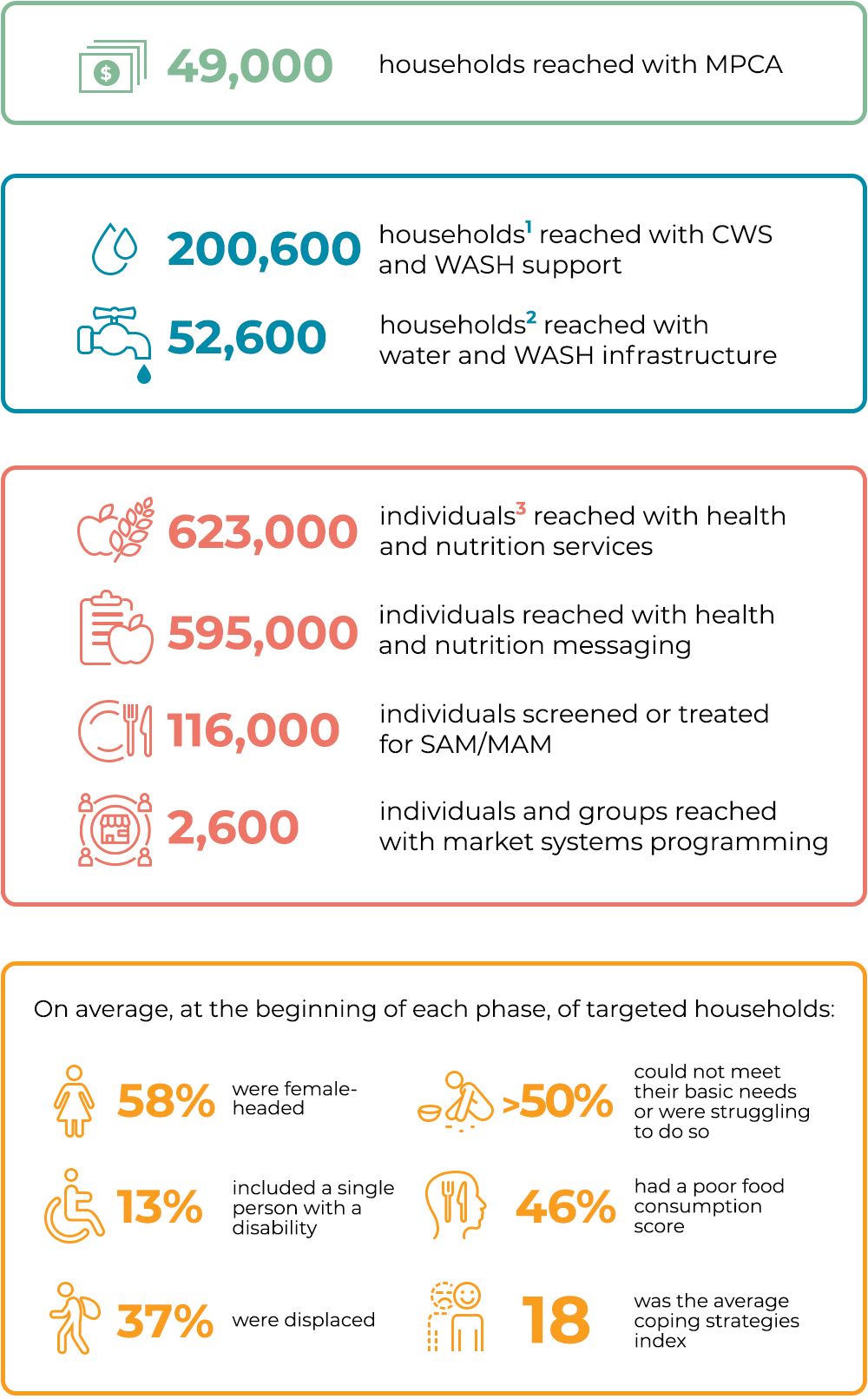

BRCiS’ initial drought response focused on the provision of direct, lifesaving humanitarian assistance in the form of multi-purpose cash assistance (MPCA) and emergency water services. It also expanded BRCiS’ usual target population from rural communities—which BRCiS has been working with for years—to include urban IDP sites, where much of the rural population was moving.

As the crisis worsened, the UK Government, joined by QFFD and then re-joined by USAID, provided additional short-term funding across four total phases, enabling BRCiS’ programming to gradually expand to include basic health and nutrition services, the rehabilitation and construction of water points, and market-based activities. Furthermore, as the response continued, BRCiS increasingly implemented its interventions via approaches designed to strengthen the resilience capacities of local market systems and actors.

Approach to Sequencing, Layering and Integration

While BRCiS’ resilience-building activities are usually sequenced, layered, and integrated (SLI), the drought response offered an opportunity to be more intentional about articulating and following this approach in an emergency setting. Collectively, the response involved both direct support to households and other interventions focused on building the resilience of Somali communities and underlying systems.

Sequencing: By beginning with more traditional humanitarian interventions such as the direct distribution of goods and services from NGOs, primarily funded by the UK Government’s Internal Relief Fund, and gradually expanding to incorporate more integrated services delivered through market activities and market systems approaches when USAID’s Economic Growth Department stepped in, BRCiS’ overall emergency response was—by default—sequenced. A further aim was to implement activities in a given community in a planned order, beginning with health and nutrition, then MPCA, followed by other interventions.

Given the limited financing available relative to the extent of need, alongside the humanitarian priority of saving lives in the emergency, community-level and household targeting—both focused on supporting the most vulnerable—was re-done at every phase. This meant that communities that improved sufficiently at one phase might “graduate out” of the emergency response while those that were most vulnerable received repeated support throughout.

Layering: In many cases, the activities were also layered, such that communities that received MPCA were also in the catchment areas for the water interventions, health and nutrition assistance, and/or market interventions. Given limitations to available funding and the extent of need, other communities received just one intervention at a time.

Integration: Since the sequencing and layering elements of the response were multi-sectoral and the BRCiS Consortium represents a coordinated group of implementers, the drought response was also integrated. The BRCiS Consortium has historically organized its activities by geography, rather than type of intervention. This has proven to reduce overlap and allow each member to develop long-term relationships with the communities with whom it works, a central component of the BRCiS approach and crucial aspect of the drought response. Each Consortium Member is responsible for targeting and implementing activities within its designated area.

Building the resilience of the market system: In addition to adopting market-based activities, the Consortium increasingly adopted a market systems strengthening approach, adapting the way in which it implemented its programming. Wherever possible, it supported existing market actors and systems, for instance facilitating public-private partnerships (PPPs) for the construction of sustainable water infrastructure and engaging with agro-dealers to provide seeds to households, rather than doing so directly. See more examples in the buttons below.

Targeting

In addition to targeting the most vulnerable communities for community and area-level interventions, each round, BRCiS Members used a community-based targeting approach to re-target households for MPCA to ensure that life-saving cash was always directed to the families who were most in need.

1 2 3

1 2 3

BRCiS conducted continual monitoring throughout its emergency drought response, including baseline, post-distribution (PDM), and endline surveys of each phase.

On average across the phases:

• Reliance on coping strategies declined from a baseline score of 18 to 13 at both PDM and endline.

• Poor food consumption immediately declined from 46% to 7% but rose to 19% three months later.

• Households who could not meet their basic needs dropped from 19% to 3% before rising to 7%.

Consistent with findings from the response’s Phase II evaluation, monitoring data from each phase repeatedly showed that the BRCiS activities had an extraordinary, positive short-term impact on MPCA households, many of whom also received other services. This represents an important achievement in a situation in which the primary objective was to save lives.

“The cash assistance was impactful and reduced the suffering of people in my community. It came at a critical time when we were facing a lot of challenges and difficulties.”

Furthermore, BRCiS managed to enter into seven hard-to-reach areas and provide emergency assistance to 1,380 households, almost none of which had received any formal support for at least a year, probably longer.

Unfortunately, especially in the earlier phases, most of the effects began to—or completely—wore off within three months, as the response was designed to be life-saving, the most direct interventions at the household level—the MPCA—were intended to last only a few months and the drought’s sustained effects were severe.

The same trend of impacts diminishing by endline was evident in later phases, though often to a lesser extent, and in some cases, the positive effects were sustained. For instance, in Phases III and IV, families’ reliance on coping strategies continued to decline not just after the intervention but even through the endline.

Still, at the end of Phase IV in September 2023, 25% of households had a poor food consumption score, which the Integrated Food Security Phase Classification (IPC) categorises as emergency level or worse, and 23% were either struggling a lot or could not meet their basic needs.

Most vulnerable groups

For the most part, the results for vulnerable groups—such as female-headed households, households with a person with a disability, and people who view themselves as internally displaced—tracked closely with the overall trend of rapid, short-term improvements that began to wear off by the endline of each phase.

Explore the chart to see some of the exceptions and nuances in this data, for instance the fact that in Phases III and IV, non-IDPs’ reliance on coping strategies continued to decline through endline, suggesting a more sustained impact, while IDPs’ reliance on coping strategies began to increase after the post-distribution monitoring survey.

This is consistent with the widespread recognition that recently displaced people are especially vulnerable during droughts, as displacement separates people from their homes, physical assets, and social support networks, undermining their resilience capacities and ability to recover when drought conditions ease. This fact is what initially prompted BRCiS to expand the drought response from its usual exclusive focus in rural areas to include urban and peri-urban IDP sites despite mixed opinions among CMU and Member staff. It also informed the design of the BRCiS-funded and e4c-led Nutrition and Mortality Surveillance System.

Impact of Sequencing, Layering, and Integration

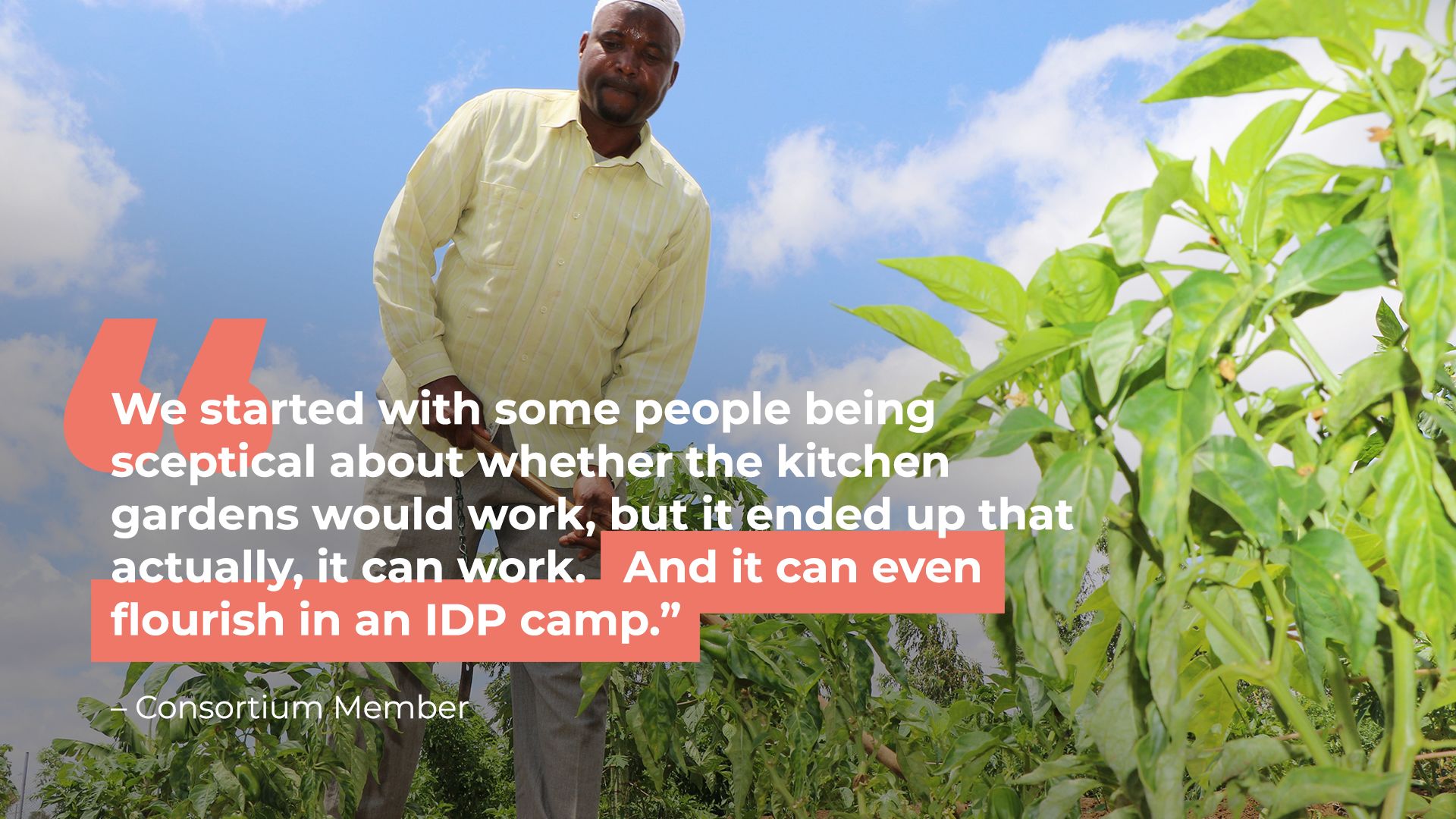

Interviews with the Consortium suggest that although the sequencing, layering, and integration was challenging to implement in the midst of an emergency, where it worked, it had a strong impact. Relationships and infrastructure built during BRCiS II laid important groundwork that Consortium Members could leverage and that supported community resilience. Innovative and market-based activities, like the kitchen gardens, were even more successful than expected.

Sequencing: Comparing one-time versus repeated touchpoints

In practice, sequencing was done whenever it was feasible. However, given the complexities associated with responding in crisis situations, such as fund distribution delays, supply chain issues, and the need to respond to immediate emergencies as they arise, sequencing within a phase did not always occur.

“Sequencing is difficult when there is a crisis, when people are dying and children are malnourished.”

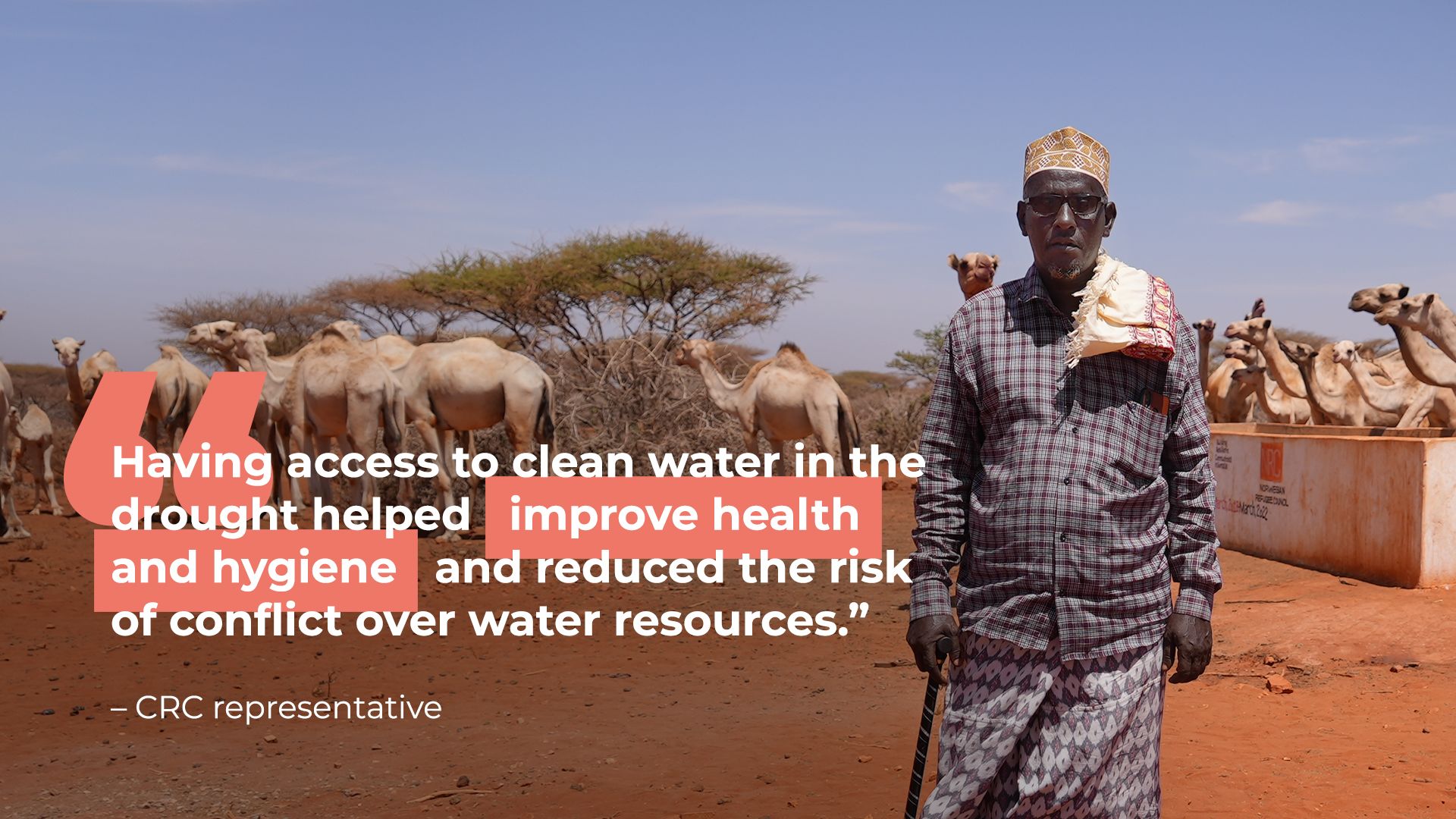

A core feature of BRCiS’ usual resilience programming, implemented throughout BRCiS I and BRCiS II from 2013-2022 is the creation of social capital, diversification of voices in local leadership, and strengthening of community structures, such as the Community Resilience Committees (CRCs) and Water Management Committees. Another major feature, especially of BRCiS II and the focus of the upcoming BRCiS III, is the creation, rehabilitation, and management of water sources.

As the drought unfolded, it was hypothesized that BRCiS’ prior resilience-building work would make the communities it has supported in recent years more resilient to the drought. BRCiS CMU, Consortium Members, and Community Resilience Committees all report that this did occur and that sequenced programming had a significant impact on BRCiS II communities. While there is some quantitative data to suggest this could be true, because the targeting changed each phase, it is not possible to verify from the quantitative data with certainty.

“Our community was able to be more resilient than other communities because the borehole dug by NRC during BRCiS II provided the community plenty of water for human and animal consumption during the drought, and the ongoing cash assistance helped our people to purchase more food.”

Photo: Omar Farouk/BRCiS.

Photo: Omar Farouk/BRCiS.

Layering of water and health and nutrition services

The layering in of water and health and nutrition services, core aspects of BRCiS’ usual early warning early action and resilience programming helped to cover basic needs that cash alone cannot address. Both community water subsidies (CWS) and the health and nutrition services were very effective in saving lives and enabling individuals and communities to maintain and even build their resilience.

Community Water Subsidies

BRCiS has been implementing CWS, an approach that builds communities’ skills to negotiate directly with water companies for emergency water procurement, since 2017. This past experience, validated through a study conducted by the BRCiS CMU, offered a good indication that CWS would be a relevant, appropriate, and cost-saving intervention for BRCiS’ emergency drought response. Ultimately, CWS was one of the response’s most impactful, empowering, and cost-effective interventions. In addition to being both life-saving and systems supporting, water companies offer communities better rates than they offer to humanitarian actors, and the direct link enables more rapid service delivery.

Water infrastructure

Two CRC representatives explained how the water infrastructure projects—the borehole constructed during BRCiS II, mentioned above, and a drainage system put in during the emergency response—impacted their communities’ well-being. First, men and women from the community obtained short-term employment opportunities on the construction sites. Second, the projects not only paid immediate dividends for the communities in terms of protection against floods—which often follow drought when the earth hardens and can no longer absorb water—and access to clean, safe water, but these positive effects will be sustained, lasting over the long-term. Furthermore, they support community resilience by reducing risks of other compounding shocks that drought can induce, such as conflict.

Photo: Omar Farouk/BRCiS.

Photo: Omar Farouk/BRCiS.

Integrating services and strengthening market systems

As BRCiS’ emergency response progressed, especially after USAID re-joined the effort in Phase III, Consortium Members further integrated their services and adapted their implementation approaches to strengthen the resilience of local systems. This included adding market-based activities to support the continuity of local food production and prevent a drought-induced collapse of local markets as well as transitioning existing programming toward private sector-led approaches. This enabled BRCiS to simultaneously meet immediate humanitarian needs while at the same time supporting the underlying market system.

For example, while BRCiS has historically undertaken CWS for emergency water provision and water infrastructure activities for sustainable water solutions, the Consortium has increasingly adapted these to be implemented through PPPs. In addition, the market systems interventions included targeted activities with a range of different participants including financial service providers, agro-dealers, farmers, communities, and households.

There was initial uncertainty among some staff members about the appropriateness of rolling out market-based programming in the midst of a deep and sustained drought, when there is a real risk of people dying. While BRCiS’ philosophy is that these approaches enable activities to be simultaneously life-saving and system-supporting, they can be technically challenging, were new for many Consortium Members, and are generally believed to require more time to implement.

Indeed, in practice, the integration of activities and implementers had varied success. It was not always possible for Members to build their capacity and effectively implement these novel approaches while responding to an evolving crisis, and while many received support from both the CMU and their organizations, more time was needed for many staff to learn the dynamics and intricacies necessary to adopt these activities and approaches fully.

While an evaluation of the response’s survey data did not reveal any major differences in the immediate effect of different intervention types on key indicators such as the Reduced Coping Strategies Index were detected, this may be due to limitations in the available quantitative survey data.

Impact data is not yet available, since the effects of market systems resilience support often takes longer to manifest than humanitarian interventions. However, the Consortium’s collective experience suggests that one activity was particularly effective.

Kitchen Gardens

Kitchen gardens were initially implemented to provide families with home-grown, nutritious food as a supplement to the direct distribution of aid. The BRCiS Consortium partnered with agro-dealers to encourage a greater supply of more nutritious seeds and vegetables and to train the women on how to implement the gardens. In addition to helping households diversify their diets within a relatively short time frame, BRCiS Members were surprised to find a secondary positive effect: many people ended up growing surplus vegetables that they could sell in the market.

Still, some cynicism around the relevance and appropriateness of kitchen gardens remains. As one key informant argued, “As soon as the rains come back, they'll go back to eating meat and milk.”

Two of the most effective qualities of the BRCiS Consortium are its eagerness to learn and agility in adapting its activities accordingly. The Consortium’s flexibility and the donors’ flexible, emergency grants enabled Members to effectively provide services to their communities.

While the CMU worked to encourage collaboration and learning amongst Consortium Members, the Members did not always have the time to engage and share their experiences on the ground with one another amidst the demands of coordinating a crisis response. Similarly, Consortium Members were not always able to absorb learnings gleaned from the learning products published by the CMU. Therefore, in order to facilitate rapid uptake, the CMU incorporated lessons learned from studies and experiences of other Members into their directives. Additionally, one of the CMU’s learning products stood out as having prompted significant change amongst the entire Consortium and beyond: the study on Community Water Subsidies.

Given the extreme need in Somalia and the desire of multiple donors to support BRCiS’ effort, BRCiS' emergency drought response became a strong example of how multiple donors with different interests can come together to achieve something greater than any of the donors initially expected. For instance, although BRCiS has been implementing SLI for some time, the UK Government and QFFD’s focus on humanitarian programming, combined with USAID’s attention to markets pushed the Consortium to strengthen its overall SLI approach, especially the integration component, and apply it more fully in an emergency setting.

In retrospect, BRCiS’ sequenced, layered, and integrated emergency drought response achieved the primary goals in any humanitarian crisis: saving lives and reducing suffering.

At the same time, the depth and extent of this catastrophic drought and limited available funding meant that in each phase, only the most immediate, short-term needs of the most vulnerable people could be met. While there were rapid improvements after each distribution, by the Phase IV endline in late September 2023, 25% of Phase IV households still had a poor food consumption score. This does not even capture the extent to which the vast number of people deemed—through a difficult and heart-wrenching process—not needy enough continue to struggle to survive.

"BRCiS' work is just a drop in the ocean."

Despite the need to build longer-run resilience, the dire circumstances meant that the Consortium was constantly responding to new crises, leaving little time to collaborate to integrate learnings, build capacities of the Members, or fully implement market systems-based approaches. While it can be difficult for implementers to build the technical capacity and relationships to implement new activities within six-month emergency funding cycles, this experience demonstrated that the Consortium is well-placed and motivated to try new things, even in complex emergency contexts, and that a multi-donor relationship can help fast-track the adoption of innovation in such situations.

Continuing to invest in learning and adaptation strategies and systems, members’ technical capacity in novel ways of working, and nurturing local networks with the private sector and other market actors during times of relative stability—for instance between now and the next major drought—will enable BRCiS and other stakeholders to mobilize even more smoothly and effectively in innovative ways during future emergency scale-ups.

“To implement market-based activities, you need to build relationships with private partners. It takes time, especially when the intention is not to give money but for them to act as a partner and also invest some of their money. One of the challenges has been the lack of time to build these relationships, these linkages.”

Still, there is general agreement that because the financing for these interventions was received from USAID Somalia’s Economic Growth Department, a funder that does not provide humanitarian relief in its remit, the market systems approach did not—as was feared—divert resources away from saving lives but rather augmented the emergency activities.

Furthermore, stakeholders—including the BRCiS CMU, Members, and donors—agree that protecting the resilience of Somalia’s markets and economy is the only way to rebuild in a way that strengthens the resilience of the Somali people and reduces dependence on humanitarian aid.

Based on this experience, there is a collective sense of excitement and optimism about the potential of building capacity to adopt more integrated and market systems-based service delivery approaches moving forward, including through engaging further with market specialists, especially now that drought conditions are easing and people and organizations can start making plans for the future once more.

Credits

Published November 15, 2023

Written, designed and developed by Untethered Impact with the support of Bell Media Group for BRCiS. Photos by Abdikadir Mohamed/NRC unless otherwise noted.

For more information about BRCiS, please contact Perrine Piton, BRCiS Chief of Party.

Learn more about BRCiS’ work building resilience and responding to drought through our website and other interactive reports: Between a shock and a hard place, and Peaks and valleys, and Feeding insights. Learn more about our approach to Community Water Subsidies through our learning report.

Donors

BRCiS Consortium