Introduction

With limited ability to verify the extent of widespread reports of malnutrition and death emerging as the 2021-22 drought emergency in Somalia unfolded, in July 2022, with funding from the UK Government and USAID, the BRCiS Consortium supported Evidence for Change (e4c) in rolling out the Nutrition and Mortality Monitoring System (NMS), a health and nutrition sentinel site surveillance system.

Based on long-standing good practices in public health and humanitarian response, the NMS works with an established network of community health workers (CHWs) to conduct periodic household visits and collect data in a limited number of purposively selected sentinel sites. Compared to other nutrition and mortality data sources which are conducted less frequently, the NMS can provide ongoing, near-real-time updates on evolving crises, detect and describe current and emerging threats to health and nutrition, and determine the coverage and adequacy of a humanitarian response.

Fitting the NMS into Somalia’s existing surveillance context

The design of the NMS prioritizes flexibility, purposive sampling, independence, and lightweight review and processing requirements at a relatively low cost. This allows it to fill a critical gap in Somalia’s otherwise strong base of existing food security, drought, and displacement monitoring systems, which include FSNAU, the IPC system, and the CCCM cluster. In fact, the NMS drew on the CCCM Cluster’s New Arrival Tracking Dashboard to identify its sentinel sites.

Photo: Abdulkadir Mohamed/NRC

Photo: Abdulkadir Mohamed/NRC

Unlike other surveys which are designed to be representative of the whole population, the NMS sites were purposefully selected to contain high concentrations of newly arrived internally displaced persons (IDPs), known to be among the most vulnerable drought-affected people, having been uprooted from their homes and undertaken perilous journeys. In addition to providing insight into the status of individuals in new camps in urban centres, sampling new arrivals also provided some insight into what was happening in the IDPs’ rural origins when they left—often areas that humanitarian actors cannot access and about which there is scarcely any information beyond speculation.

Exploring NMS sentinel sites in Somalia

The initial round of data was collected from July 18-August 2, 2022 in 11 IDP sites in three districts of Somalia. Camps were added and adjusted as funding allowed. By the end of the six rounds of monitoring, a total of 34 IDP sites had been sampled in seven areas.

“We ask where the IDPs are coming from, so we are able understand what may be happening in those areas of origin. Most of them come from locations that are inaccessible or hard-to-reach where there are no humanitarian services”

Banadir, the administrative area encompassing Mogadishu, was one of the first three areas selected. Monitoring there began with three sites in Kahda and later expanded to include another three sites in Kahda, both led by ACF, and six sites in Daynille, led by Concern Worldwide and IRC. In Kahda, most of the surveyed individuals had originated from nearby Lower Shabelle, but in Daynille, most had come from Bay Region.

A large proportion of new arrivals in the monitored sites in Baidoa and all of those in Diinsoor, the other two areas selected for monitoring from the outset, had also originated elsewhere in Bay Region, a hotspot of the displacement crisis. Monitoring was led by GREDO and SOS in Baidoa and GREDO in Diinsoor.

Kismayo—as well as Dollow near the Ethiopian border and Galkayo in north-central Somalia—were some of the sites added later, in rounds 3, 4, and 5. Data collection in these areas was led by SCI, Trocaire, and IMC, respectively.

Integration with existing public health systems

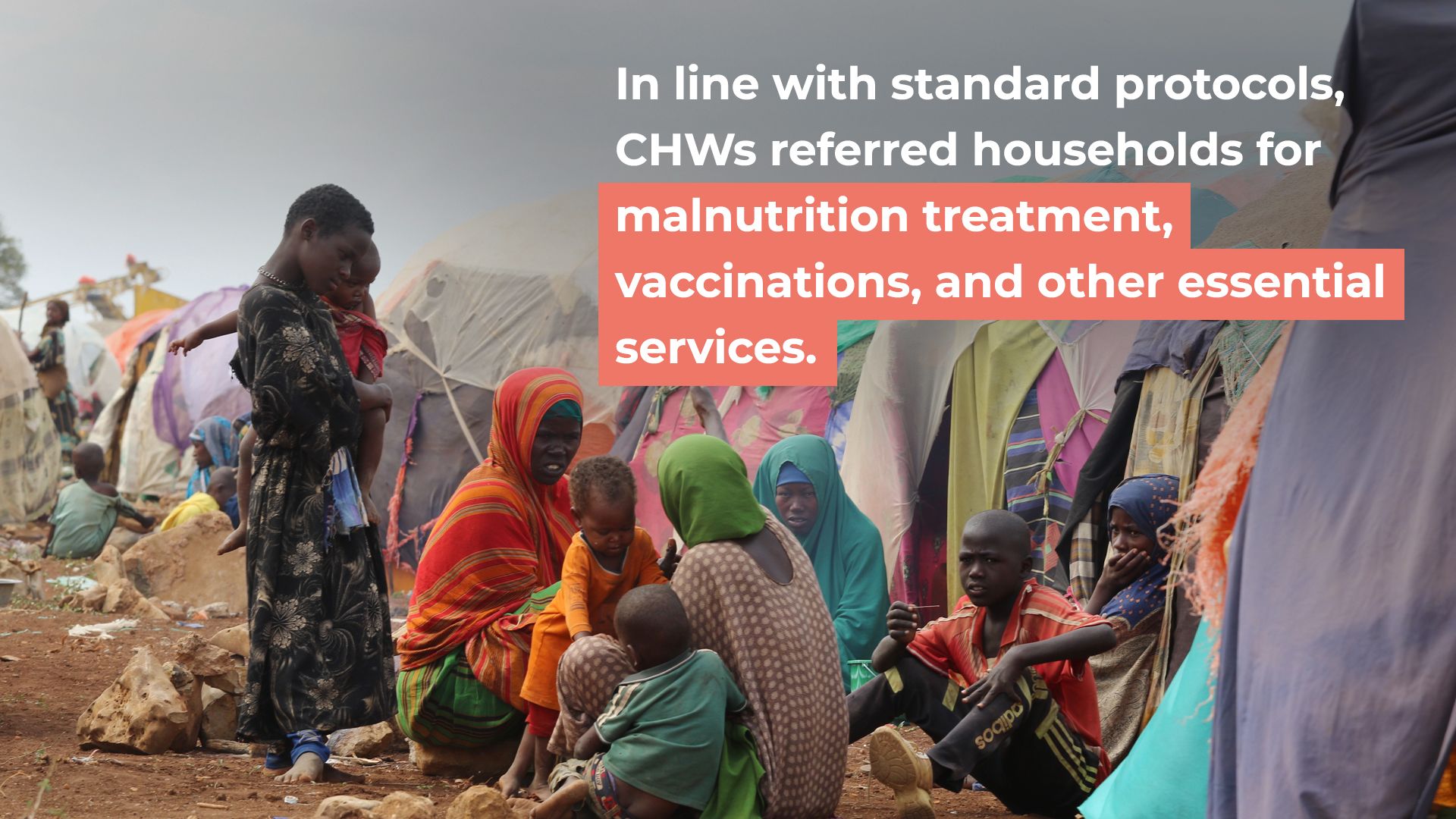

Data was collected from all households present at each site in partnership with existing Community Health Workers to support NGOs in maintaining a culture of working through CHWs and to encourage CHWs to maintain good public health and outreach practices through regular household visits.

Photo: Abdulkadir Mohamed/NRC

Photo: Abdulkadir Mohamed/NRC

The same sites were monitored over multiple rounds to provide an understanding of how new arrivals’ circumstances evolved. The initial expectation was that because the data collection process was integrated with referrals, after about three rounds, the NMS would demonstrate sufficient improvement, and the site could be dropped and replaced by another site. In practice, the indicators improved more slowly than anticipated, and most of the initial sites were followed for five rounds.

In practice, the number of households in each site ebbed and flowed, as displaced people are a highly mobile population. Similarly, the sites and camps represented in each area changed across rounds as funding and partnerships evolved. Both of these factors should be considered when interpreting the NMS results.

Nutrition monitoring

The first round of NMS data collection was rolled out in Baidoa, Dinsoor, and Khada in January 2022, after FEWS NET and FSNAU had already raised the alarm on the risk of famine. Consistent with existing reporting, in all three locations, Global Acute Malnutrition (GAM) rates, as measured by mid-upper arm circumference (MUAC), exceeded the IPC Critical – Extremely Critical threshold.

BRCiS and e4c immediately circulated the findings among BRCiS members and flagged the results to the Health and Nutrition Cluster. Given e4c’s reputation for rigorous and independent analysis, the initial results were widely trusted and accepted.

Photo: Abdulkadir Mohamed/NRC

Photo: Abdulkadir Mohamed/NRC

While the results were not necessarily actioned everywhere, this new information sparked BRCiS and the Caafimaad Plus Consortium to develop strategies to reach those in need. These included deploying emergency mobile teams to provide immediate health and nutrition support to displaced families.

Photo: Abdulkadir Mohamed/NRC

Photo: Abdulkadir Mohamed/NRC

While a range of factors contributed to the improvement in nutritional status over time in all of the surveyed districts, measured here as a reduction in GAM rates, the integration of the CHWs in the NMS was an important component. Regular and repeated data collection for the NMS served the dual purpose of a public health screening, such that any time a child was identified as being sick, malnourished, or unvaccinated, the CHW enumerator referred them for treatment.

WASH monitoring

Following Round 2, collected from 21 August to 10 September, WASH results related to the adequacy of drinking water and access to latrines were flagged to the WASH cluster.

It is fairly clear from the area-level data that the results were actioned in some cases, for instance with the provision of latrines in Dinsoor.

Photo: Abdulkadir Mohamed/NRC

Photo: Abdulkadir Mohamed/NRC

In other cases, the influence of the NMS findings may have been more minimal or less direct—the NMS results being only one among the host of inputs that humanitarian actors normally use to make their response decisions.

Whether or not the findings were always actioned, the NMS made a valuable contribution as an objective data source that could track both the extent of need caused by the drought as well as the response.

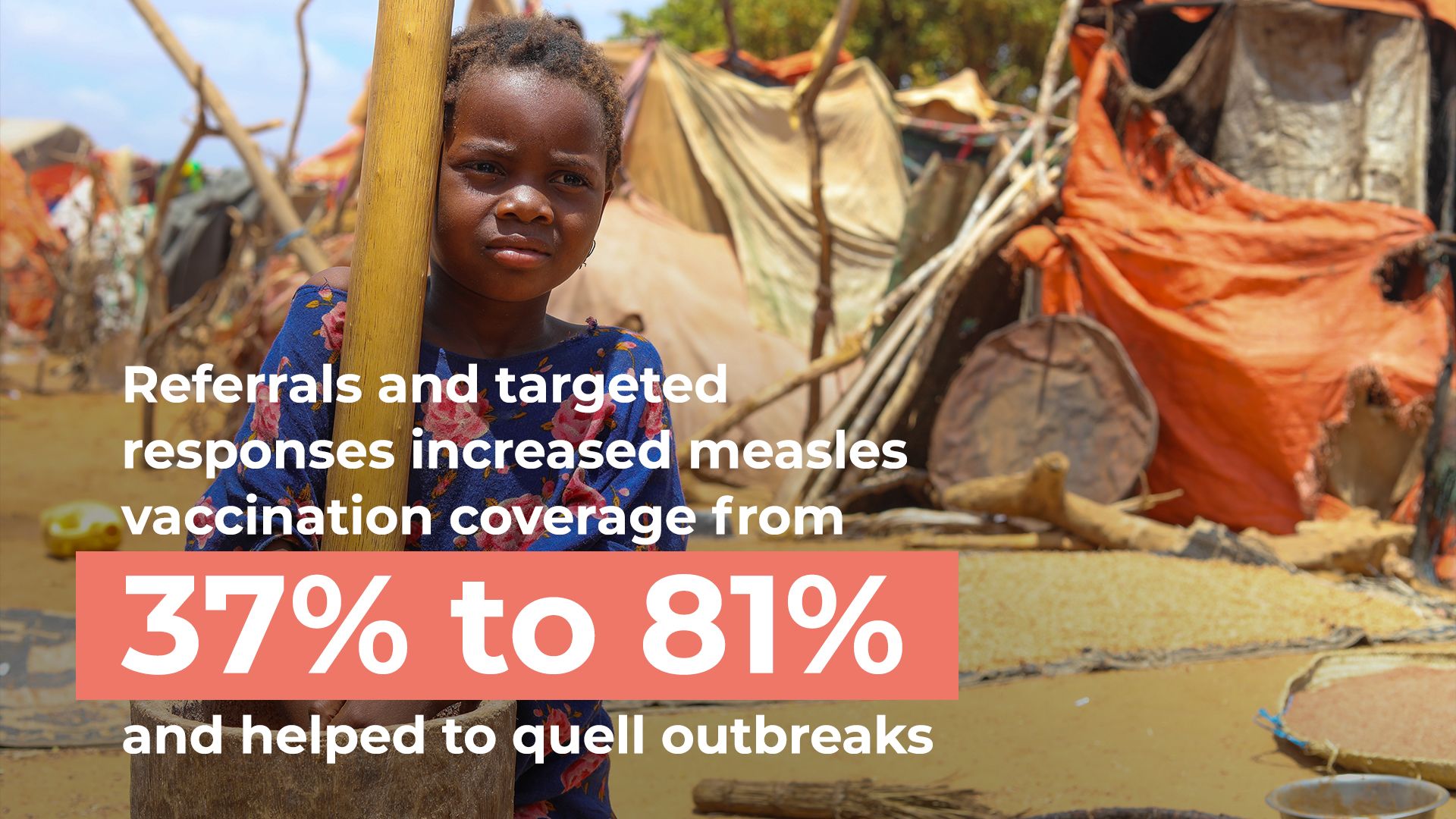

Vaccinations and morbidity

In addition to the built-in referrals, the dissemination of data emerging from the NMS in relevant forums began to spark specific responses and targeting of planned actions from stakeholders with the resources and mandates to respond.

This led to increased vaccination coverage and decreased morbidity for both measles and cholera/acute watery diarrhoea (AWD).

Photo: Abdulkadir Mohamed/NRC

Photo: Abdulkadir Mohamed/NRC

There was some geographical variation, for example, when findings of a relatively high prevalence of suspected measles in Baidoa coincided with the planning stages of a local vaccination campaign, the Caafimad Plus Consortium chose to purposefully cover the NMS data collection areas.

Furthermore, demonstrating its ability to provide near-real-time information about the situation on the ground for timelier response, in Round 6, the NMS picked up a measles outbreak in Kahda IDP site.

Collaboration

While interest from certain donors such as FCDO was high early on, when there was a significant concern about the risk of famine, the NMS reached an increasing number of stakeholders with each round of data collection, as the scope of dissemination of the results widened and additional indicators and sites were flagged and brought forward to the Humanitarian Donor Group, the inter-cluster coordination group led by OCHA, and specific clusters.

Recognizing the need to scale up the system to cover additional sites and districts, the Caafimaad Plus Consortium mobilized additional funding from its donor, ECHO, and support from its members. As a result, the NMS was able to expand to cover 31 sites across 6 districts by Round 5 in March 2023. Furthermore, Caafimaad, through collaboration with the Somali Cash Consortium, was able to use NMS findings to target newly displaced populations in Mogadishu and Dollow IDP sites for cash assistance using an integrated approach.

In addition to significantly expanding the scale of available information, the collaboration between BRCiS, Caafimaad Plus, and e4C is a powerful example of the benefits of coordination and co-funding in the context of a humanitarian crisis.

Bringing the facts to light

While it was important for the NMS to provide ongoing surveillance to flag emerging needs and to provide near-real-time information on the status and adequacy of the humanitarian response, one of its primary purposes was to offer an objective, data-based report on the death rates found in the sentinel sites and the extent of the crisis in terms of the risks of excess mortality.

Despite increasing reports that the situation was moving toward famine, the results from the NMS surprisingly suggested that some of the media reports were overstating the severity of the crisis. Although the NMS’s July 2022 mortality figures were at emergency/IPC Phase 4 levels—including an Under-5 Death Rate (U5DR) of 3.0 and a Crude Death Rate (CDR) of 0.9—the peak of the crisis did not actually reach the levels observed by the NMS in 2017.

However, by monitoring the situation over time, the NMS also revealed that the duration of elevated mortality was longer than in 2017, the crisis lasted a longer period of time, the humanitarian response overall was slower and more lethargic, and the collective mortality burden overall was still very high.

“These findings illustrated the importance of having a mortality surveillance system. If people were looking at this without survey data and without surveillance data, everyone would have assumed—including myself—that mortality was peaking at higher levels than it actually did. I personally would have assumed that mortality was quite a lot higher.

Having good data is very important to either confirm or deny people’s assumptions. And for the humanitarian response, that should be our number one objective: reduce excess mortality, followed by reducing suffering and preserving dignity. So we definitely should be going out and measuring it to find out how we’re doing.”

Reminders for humanitarian response and lessons for famine monitoring

At the end of the day, the experience from the 2022-2023 crisis provided reminders for humanitarian actors and famine watchdogs about the unreliability of weather forecasts, the role of conflict in turning droughts into major crises, and the importance of getting the basics right. In the current conversation around the role of cash in humanitarian emergencies, the results from the NMS also make an important argument for the value and need for essential service provision, such as latrines and vaccinations, in crisis contexts.

Photo: Abdulkadir Mohamed/NRC

Photo: Abdulkadir Mohamed/NRC

“The NMS helped to shine a light on deficiencies in basic needs and motivated action to happen. FCDO and other donors and NGOs were making decisions based on it. It also helped illustrate that the most vulnerable population is indeed the newly arrived IDPs. As a result, FSNAU adapted their sampling approach to better account for new arrivals and ensure they weren’t diluting the IDP sample with protracted IDPs.”

Application to other contexts

As a relatively independent, flexible, and lightweight monitoring system that requires minimal data processing time, the NMS has wide applicability for other contexts. In particular, its focus on interviewing newly arrived IDPs makes it especially appropriate for situations in which humanitarian access is not possible and stakeholders are trying to understand areas where there is limited information available.

Photo: Abdulkadir Mohamed/NRC

Photo: Abdulkadir Mohamed/NRC

Based on this experience, the various partners recommend following a similar structure, with the monitoring system designed and implemented by independent consultants that are well-networked and trusted by decision-makers in the local context but run through and with the support of NGO consortia who can help with streamlining funding and dissemination of the findings, enabling the results to quickly reach decision-makers. This approach offers a careful balance between ensuring sufficient independence from sometimes political processes such as famine declarations while still being integrated enough for the information to be used.

BRCiS: Looking ahead

In an emerging drought context, timing is everything. That is one reason integrating the near-real-time nutrition and mortality monitoring proved to be an invaluable asset during the 2021-22 response. An important caveat, however, is the time it takes to start up both a monitoring system and humanitarian response once actors realize it is needed. While the Government of Somalia declared a state of emergency in November 2021, the NMS was only implemented in July 2022. As is evident from the graphics shown above, the peak of the crisis was likely missed.

“Was it timely? We don’t know. We might have missed the peak of the crisis because there are gaps between the data that was collected in 2017 and now.”

Photo: Abdulkadir Mohamed/NRC

Photo: Abdulkadir Mohamed/NRC

Like most other early warning indicators, the NMS would offer even greater value to BRCiS, Caafimaad Plus, donors, and other stakeholders if it were integrated into a continuous early warning early action system. Incorporating frequent sentinel trend analysis during periods of relative stability would not only provide a baseline for future emergencies but ensure that a system is in place and ready to capture information on the period during which a crisis is ramping up—and peaking.

BRCiS and FCDO are now coordinating to see how BRCiS might incorporate this type of data into its existing Early Warning Early Action system.

“It should be something we invest in long term that is flexible, can be scaled up and scaled down, and that can inform response, advocacy, and objective information needs internally and externally. It should not just be a drop in the ocean now and then, but a long-term tool that gives us the whole picture of the situation.”

Credits

Published October 31, 2023

Written, designed and developed by Untethered Impact with the support of Bell Media Group for BRCiS.

All of the NMS reports, including the Synthesis Report, are publicly available on ReliefWeb and e4c’s website..

For more information about BRCiS, please contact Perrine Piton, BRCiS Chief of Party.

Learn more about BRCiS’ work building resilience and responding to drought through our other interactive reports: Drought interactive report, Between a shock and a hard place and Peaks and valleys.

Donors

BRCiS Consortium

Caafimaad Plus Consortium