Peaks and valleys amidst mountains of need

BRCiS' drought response and vision for climate resilience in Somalia

Encroaching

famine

The story of one woman

among millions

58-year-old Sangabo Hassan Mohamed has lived all her life in a village in Bakool Region of Somalia—the same village where she raised her daughter and three grandchildren. Primarily a pastoralist, she owned over 175 goats as well as a big farm on which she grew sorghum, maize, and cowpeas. She felt she lived a good life, but suddenly, everything changed. The drought came.

An earth dam in Baidoa that dried up in the drought. Photo: Abdulkadir Mohamed/NRC.

An earth dam in Baidoa that dried up in the drought. Photo: Abdulkadir Mohamed/NRC.

At the same time, Sangabo’s daughter, Xalwo, became very ill and could no longer walk long distances. With no hope of recovering either of their income sources in the foreseeable future, the two women were forced into an impossible decision. They left Xalwo behind to save the children.

The desolate landscape through which Sangabo and her grandchildren walked to reach Baidoa. Photo: Omar Farouk/BRCiS.

The desolate landscape through which Sangabo and her grandchildren walked to reach Baidoa. Photo: Omar Farouk/BRCiS.

It took Sangabo and her three grandchildren eight days to walk the 150 hot, dusty kilometres to reach an IDP camp in Baidoa Town. While they managed to reach Baidoa alive, their donkey did not. Sangabo is grateful to have arrived and optimistic about their future, but she now faces a new set of challenges.

We came here with nothing except the clothes we are wearing and some basic household items. We have no shelter, food, or water. I have collected sticks, abandoned plastic sheets, and pieces of clothes to construct a temporary makeshift shelter for my children. It’s a new place with a new challenge, and I don’t know where to start, but I hope we will survive here. I pray for my daughter and wish her a quick recovery to come join us.

Sangabo sits with her grandchildren in the shade of the donkey cart that helped bring them from Bakool to Baidoa. Photo: Abdulkadir Mohamed/NRC.

Sangabo sits with her grandchildren in the shade of the donkey cart that helped bring them from Bakool to Baidoa. Photo: Abdulkadir Mohamed/NRC.

I am an old person—I have lived through many drought situations and experienced difficult living conditions. But I have never witnessed a drought as devastating as this. We had no rains and no pasture for our livestock. Our crops were devastated, and all of my goats died in front of my eyes.

Sangabo constructs a temporary, makeshift shelter made of sticks, clothing scraps, and plastic sheets. Photo: Abdulkadir Mohamed/NRC.

Sangabo constructs a temporary, makeshift shelter made of sticks, clothing scraps, and plastic sheets. Photo: Abdulkadir Mohamed/NRC.

It was a horrific journey. Along the way, we stopped several times because of our severe hunger and lack of water. My grandchildren were crying for food, but I had nothing to give them apart from some wild fruits. We walked as much as we could each day, but hungry and thirsty people cannot walk enough. At night, we stayed by the roadside. I didn’t sleep so I could protect my grandchildren from the risks of hungry, deadly animals.

Sangabo's shelter will look much like her neighbours', covered in foraged plastic sheets, when she is finished. It will house her and her three grandchildren during their time in Qaydaradey IDP camp. Photo: Abdulkadir Mohamed/NRC.

Sangabo's shelter will look much like her neighbours', covered in foraged plastic sheets, when she is finished. It will house her and her three grandchildren during their time in Qaydaradey IDP camp. Photo: Abdulkadir Mohamed/NRC.

Sangabo’s story is one among millions—7 million who have been affected by the drought and 1 million who have been forced to flee.

Drought monitoring bodies have been forecasting and on the brink of officially declaring famine for months now. With cereal production at less than 50% of the long-term average, deaths of over 3 million livestock, and sky-high food prices, they are now predicting a sixth failed rainy season.

Humanitarians are recalling scenes from the famine of 2011, with more than half of the country's children malnourished, widespread illness, and an increasing number of drought-related deaths.

At this point in time, the available data does not accurately estimate or represent the extent of mortality across the country, as data collection is only possible in areas with humanitarian access

Real-time nutrition and mortality monitoring

To provide ongoing, near-real-time information on the evolution of the crisis, detect and describe current and emerging threats to health and nutrition, and determine the coverage and adequacy of the humanitarian response, BRCiS has established a Nutrition and Mortality Surveillance (NMS) system. The system involves monthly data collection in 4 sentinel sites with newly displaced IDPs: Kahda, Baidoa, Diinsoor, and Daynille. The first two rounds of data, covering late July and late August to mid-September, have confirmed that the health and nutrition situations in these sites are very serious.

While there have been improvements in the delivery of vaccination and malnutrition treatment services, serious gaps persist.

As of late August/early September:

- Acute malnutrition was around 21%, exceeding the 15% threshold for an extremely critical situation.

- Vaccination rates remained low, at around 40% for measles and 30% for cholera.

- Around 4% of children were suspected to have measles and 8-20%, depending on the site, to have acute watery diarrhoea (AWD).

- Under-5 death rates were at emergency levels (2.2/10,000/day).

Click the buttons to read our recommendations.

BRCiS'

drought

response

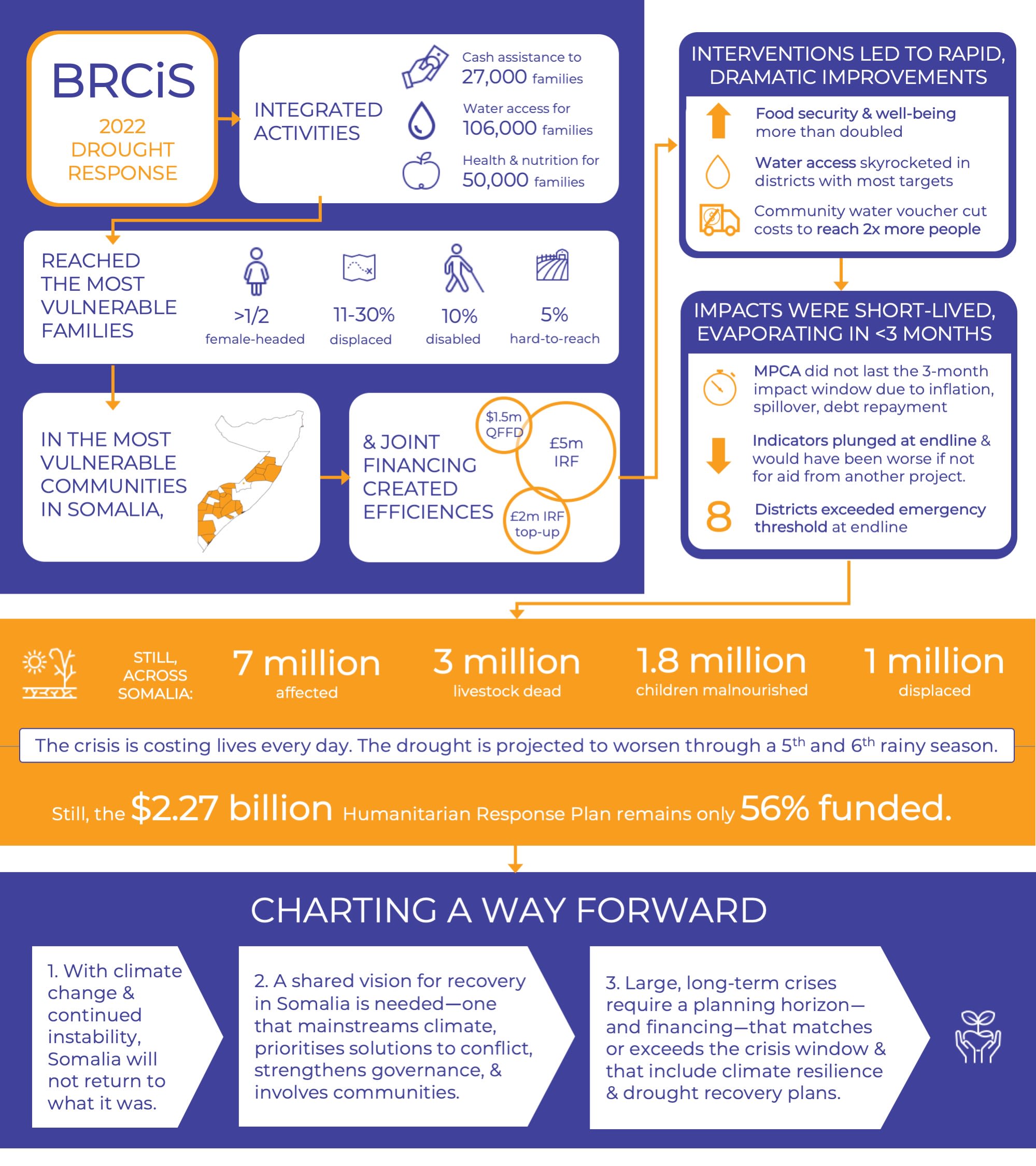

BRCiS’ drought response started as early as January 2022 and supported rural communities with an integrated and community-led response throughout the year. It aimed to address urgent and severe humanitarian needs of the most vulnerable drought-affected people and to reduce the risks of mortality, morbidity, and other irreversible aspects of the crisis.

Click to learn more about our approach.

Cash

Assistance

For 27,000 households

The project provided 27,000 households with a three-month lumpsum multi-purpose cash assistance transfer of USD180-270, following Somalia Cash Working Group guidance. This was rolled out in three parts: the initial response, a scale-up via the Crisis Modifier mechanism, and a funding top-up provided by the UK Government. The scale-ups enabled the project to reach more than twice as many households as initially planned.

Click to read participants' perspectives.

Explore the data story to learn more.

The top-up response included a pilot in hard-to-reach areas that reached 1,380 households. The project evaluation confirmed that these families were especially vulnerable and underserved, with only 5% having received humanitarian support in the previous year. Meeting the needs of these extremely vulnerable people may be worth the costs, logistics, and risks of expanding into these new and challenging areas.

Water

For 106,000 households

The project included two types of water interventions: 60-90 days’ worth of community water vouchers for 67,000 households and rehabilitated and new water infrastructure for 39,000 households. Both activities were designed to be community-led and to meet current needs while building resilience.

The water activities were carried out in all districts covered by the initial cash response but were more heavily concentrated in some districts than others. In districts where water interventions were most concentrated, water access increased significantly.

Community water vouchers

Unlike typical water trucking, the community water vouchers were community-led and owned. Community water management committees were empowered to be the main decision-makers, identifying local suppliers, negotiating terms and prices, and monitoring the timely delivery, quantity, and quality of water. Implementing partners, state-level Ministries of Water, and the community at large were all stakeholders, but at the end of the day, suppliers were accountable to the communities, reducing resources and headaches that come when implementing organisations have to serve as an intermediary.

A young woman washes her clothes using water provided through a community water voucher. Photo: Abdulkadir Mohamed/NRC.

A young woman washes her clothes using water provided through a community water voucher. Photo: Abdulkadir Mohamed/NRC.

A qualitative evaluation of the community water voucher found:

- it cost half as much as conventional water trucking, allowing the project to reach twice as many people for the same cost;

- it was five times faster to implement, taking an average of six days to procure compared to 33, and provided local employment for casual labourers;

- participating communities were more educated about and able to stand up for their rights, and many prioritised marginalised groups such as people with disabilities and the elderly when fetching water.

Hawo Mohamed Ibrahim, mother of seven children, and her friend stand amongst other women waiting for their jerrycans to be filled from a water truck in Ifo 2 IDP camp in Baidoa. Photo: Abdulkadir Mohamed/NRC.

Hawo Mohamed Ibrahim, mother of seven children, and her friend stand amongst other women waiting for their jerrycans to be filled from a water truck in Ifo 2 IDP camp in Baidoa. Photo: Abdulkadir Mohamed/NRC.

If the company supplies less water than expected, it will be encouraged to bring the remaining amount. Otherwise, it will not be paid with any money. If this process fails, we will terminate the contract with the organisation.

A group of IDP women chat as they collect water. Photo: Abdulkadir Mohamed/NRC.

A group of IDP women chat as they collect water. Photo: Abdulkadir Mohamed/NRC.

The people are given the right to choose their water committees and to include all different groups: the vulnerable, the weak, people living with disabilities, and minorities. Through this process, these people feel that they are part and parcel of the community, and no one is segregated. In addition, these people have a representative in the committee and can forward any complaints to them.

Water infrastructure: Abdi's story

Health &

Nutrition

For 50,000 households

Fatima, a community health worker at Towfiq PHU health clinic in Baidoa, provides medicine and advice to a mother with a sick and malnourished child. Photo: Abdulkadir Mohamed/NRC.

Fatima, a community health worker at Towfiq PHU health clinic in Baidoa, provides medicine and advice to a mother with a sick and malnourished child. Photo: Abdulkadir Mohamed/NRC.

In addition to the Nutrition and Mortality Surveillance system, the IRF project’s health and nutrition activities included fixed and mobile clinics, awareness, and surveillance targeting 6,700 households in Afgoye, 3,600 households in Wanlaweyn, and 40,000 households in Baidoa. The activities specifically targeted women and children, who tend to bear the brunt of the drought’s impacts.

Health and nutrition: Shariffa's story

Towfiq PHU in Baidoa serves a catchment area of around 25,000 people including Shariffa. With malnutrition on the rise throughout the district, Shariffa's children were two of as many as 100-120 children that the clinic screens for malnutrition on a daily basis. While the addition of a mobile clinic in Eladow IDP camp has allowed Towfiq PHU to scale up and screen an even larger catchment area, it has also served to increase the clinic’s caseload.

The clinic can treat standard cases of malnutrition, but children with complications are referred to the main hospital’s stabilisation centre. However, there is no ambulance to transport the referred cases, and the hospital’s paediatric ward is so taxed, it is overflowing into outdoor tents.

Charting

a way

forward

While BRCiS and other humanitarian responses have helped to curb an official famine so far, they are barely containing the damage. Funding has been late and remains woefully inadequate. The effects of the delayed and insufficient action are accumulating, and there is still no end in sight.

Back in April, needs were already outpacing humanitarian support. BRCiS Consortium Members and local authorities overseeing the project’s community-based targeting and registration process found targeting to be next to impossible, as almost every family in the selected communities was struggling to survive. Set against a limited budget, they ultimately fine-tuned the criteria enough to distinguish the most absolutely vulnerable families, but they had to turn away many deserving families in the process.

Even the families who are selected into a humanitarian project are not starting from zero. They bring with them accumulated debts and losses that humanitarian support must make up. As many as two-thirds of BRCiS IRF households used their cash assistance to pay back debt. The project’s evaluation found that the cash transfers were insufficient to cover basic needs for the intended three months, with needs often meeting or exceeding baseline levels when households were well within the impact window.

A woman and her children sit in front of their temporary shelter in an IDP camp. Photo: Abdulkadir Mohamed/NRC.

A woman and her children sit in front of their temporary shelter in an IDP camp. Photo: Abdulkadir Mohamed/NRC.

I have experienced a lot of tribulation in my life, but none as bad as this. Out of 250 cows, all but 18 perished. I spent all my income and more buying water to trying to keep them alive. I now owe so many people so much money, I finally switched off my phone.

Now, six months later, these issues have not been resolved.

The drought is unrelenting, with needs skyrocketing so fast that humanitarian actors can’t update them fast enough.

The Integrated Phase Classification’s Famine Review Committee has issued its second famine warning.

With over one million people displaced and child malnutrition rates reaching as high as 59% in Baidoa in September, the crisis is costing lives every day.

Despite nearly a year of warning from UN and NGO partners, the current US$2.27 billion Humanitarian Response Plan remains only 56% funded.

Even within Somalia, the humanitarian crisis—which most severely affects the most marginalised groups—is not receiving the attention it deserves. The emergency is growing so rapidly, that the Federal Government of Somalia’s capacity to prioritise, lead, and coordinate the response and to hold national and international bodies accountable to their commitments and humanitarian mandates will be the basis for their legitimacy moving forward.

In 2022, even in such an extraordinary drought situation, the global community had the knowledge and capacity to have largely averted the catastrophe that is unfolding across southern Somalia.

The lack of financial follow-through from governments around the world to make this happen reveals that their good intentions shrouded empty promises. This shoulders them with responsibility for the growing death toll of hundreds

—and soon to be thousands—

of children in Somalia.

While we cannot overstate the gravity of the current situation, our job at BRCiS is to maintain a resilience mindset. In such a dark time, we see this as a mandate to preserve hope and to help chart a course out of this crisis. To do that, we, as a global community, need:

1. To acknowledge that it is unlikely that Somalia will return to what it was before the drought.

Climate change—and this drought in particular—has killed off millions of livestock, accelerated degradation of farmland and pasture which will take years to rebuild, and initiated urbanisation and protracted displacement to unequipped urban centres. Decades of conflict—including an insurgency and tensions between central and state governments—has degraded rule of law, limited state presence and capacity, intensified displacement, and exacerbated humanitarian access challenges.

2. A vision—shared by all stakeholders—for what resilience looks like in Somalia.

We need a basic, agreed frame through which to view political, development and humanitarian engagement to help align external engagement, reduce replication and costly investments working at cross purposes to each other. This shared paradigm must mainstream climate, prioritise solutions to conflict, include stronger government leadership and coordination, and involve communities.

3. A roadmap, concrete steps, and financing to get there.

Humanitarian actors, donors, and other stakeholders must recognise that large, long-term crises require more than a short-term emergency paradigm. The planning horizon—and associated financing—must account for the fact that they are starting below ground zero, match or exceed the crisis window and be founded in a resilience mindset, incorporating climate resilience and drought recovery plans.

Abdirahman Isack, a 60-year-old new arrival in Qaydar-adde IDP camp in Baidoa tells the story of his displacement. Photo: Abdulkadir Mohamed/NRC.

Abdirahman Isack, a 60-year-old new arrival in Qaydar-adde IDP camp in Baidoa tells the story of his displacement. Photo: Abdulkadir Mohamed/NRC.

Our situation is an extreme one. But all in all, we do not give up hope, for Allah’s mercies shall come through.

Written, designed and developed by Jenny Spencer. Icons by icons8.

For more information about BRCiS, please contact Perrine Piton, BRCiS Chief of Party.

For more information:

- The latest news from Consortium Members on the drought situation in Somalia

- 2022 Drought Response Impact Evaluation Report

- Community Water Voucher Learning Report

- Sentinel Site Nutrition and Mortality Monitoring Round 1 and Round 2

- More about BRCiS