Omaia worries that her loved ones will be killed

The first time she experienced Gaza being attacked was in 2014. Her neighbourhood was razed to the ground. She saw blood and dead bodies in the street. When Omaia turned 16 in May 2021, Gaza’s armed groups were once again engaged in a bloody conflict with Israel. During the bombing, she hid behind a wardrobe and did breathing exercises.

Omaia lives in the Al Sha’af neighbourhood with her grandfather, mother and father, three sisters and two younger brothers. Her father works as a stonemason.

2017: Students including Omaia are attending Arabic language class at their school, Sobhi Abu Karish in Gaza.

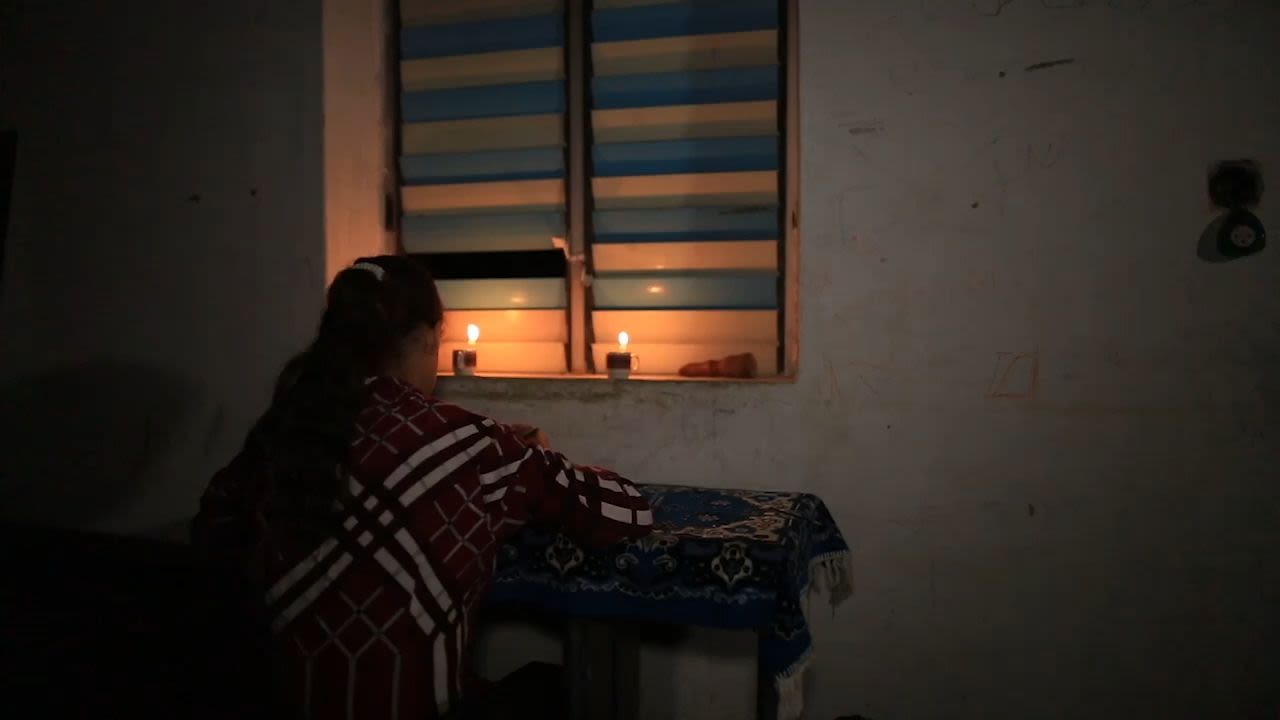

She is sitting in semi-darkness in the living room. In semi-darkness because, in Gaza, they only have electricity 12 hours a day. In the living room because she no longer uses her old room. Not after one of the walls developed a large visible crack as a result of the bombing last year.

Omaia, when are you happy?

“When I have my family around me.”

2017: Students including Omaia are attending Arabic language class at their school, Sobhi Abu Karish in Gaza.

2017: Students including Omaia are attending Arabic language class at their school, Sobhi Abu Karish in Gaza.

A birthday celebrated with bombings

“Omaia just sits in her room and wants to be alone,” her father told us anxiously when we called him in August last year.

On 19 May 2022, Omaia will turn 17 years old. But she has no great expectations for the day.

2022: Omaia has never been outside Gaza. She dreams of travelling to see the world.

2022: Omaia has never been outside Gaza. She dreams of travelling to see the world.

“When I turned 16, my birthday was ‘celebrated’ with bombings. But my dad did give me a birthday cake,” she says, and continues:

“The war in 2021 was completely different from 2014. During the first two days of bombing, I didn’t think much about it. But then I started to feel anxiety. I felt that everything was going to become more violent. I sat alone the whole time, away from my family, here in the corner. I even argued with them to avoid being with them. I started thinking that it would soon be our turn.”

"I sat alone the whole time, away from my family, here in the corner. I even argued with them to avoid being with them."

“This all happened a few days before Eid. I had been excited and was all dressed up and ready to celebrate Eid. We were supposed to celebrate with joy, but instead we fled out of fear.

“Everyone was scared and they were talking about a ground invasion. That was the worst, everyone saying ‘ground invasion’. I ran to my mother’s room and hid behind a wardrobe. I hid from the sound of the bombs. All I could do was focus on the breathing exercises I had learned in school: ‘Breathe. Breathe slowly: In. Out. In. Out…’”

Wars don't end when bombs stop falling. Help us be there for children facing trauma. Visit nrc.no/donate.

Physical and mental scars

“Palestinian and Israeli children always pay the highest price during these episodes of violence, which leave not only physical scars, but also mental ones,” said Jan Egeland, Secretary General of the Norwegian Refugee Council.

Omaia’s home was not bombed.

But the wall in her room did develop a large crack due to nearby bombing.

And now she still just wants to be alone.

The escalation on 10 May 2021 happened after weeks of growing tensions in Jerusalem, following Israel’s repeated threats to evict Palestinian families in Sheikh Jarrah.

12 May 2021: A house is targeted in Gaza City. Photo: M. Hajjar/NRC

12 May 2021: A house is targeted in Gaza City. Photo: M. Hajjar/NRC

Tensions around East Jerusalem led to intense hostility between Israel and Palestinian armed groups in Gaza. There was unrest across the West Bank, and a wave of street violence in Israeli cities between Jews and Palestinian citizens of Israel.

Rocket attacks by Palestinian armed groups were met by an Israeli military attack from the air and the sea, in addition to shelling.

The escalation lasted for 11 days. In Gaza, 261 people – including 67 children – were killed, according to the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR). Twelve of the children killed in Gaza had received support from NRC’s Better Learning Programme.

More than 2,200 Palestinians were injured. A further 27 Palestinians, including four children, died in the West Bank. In Israel, 13 civilians, including two children, were killed.

The Gaza Strip

Gaza is a narrow strip of land on the east coast of the Mediterranean. The area is about as big as a medium-sized city – 365 square kilometres. It only takes an hour to drive from one end to the other.

There are 2.1 million people living in the Gaza Strip. The majority, about 1.4 million, are Palestinian refugees from the Arab-Israeli war in 1948, and their descendants.

Decades of living under Israeli occupation and nearly 15 years under siege by Israel and Egypt have caused great suffering to the civilian population. Numerous rounds of armed conflict between Palestinian armed groups and the Israeli military have destroyed thousands of homes and businesses, and devastated critical infrastructure – electricity is only available for an average of 12 hours per day and drinking water and sewage treatment plants are often offline.

Severe Israeli restrictions on free movement and both internal and international trade have hindered economic development. According to the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics, Gaza’s unemployment rate in 2021 was 47 per cent. The World Bank estimates the poverty rate in Gaza at 59.3 per cent in 2021.

Some 63 per cent of Gaza’s population (1.3 million people) will need humanitarian aid in 2022. In comparison, 21 per cent of Palestinians living in the West Bank (0.75 million people) will have similar needs. Making things even more distressing, over 40 per cent of the population in Gaza is under the age of 15, which means that children are in particular need of protection and assistance.

“Nebraz”

“For me, the most difficult thing is this: that it still feels like I’m between two wars. It makes me feel completely empty. Numb. That’s why I mostly sit here in the corner, all to myself. I don’t want any close relationships with my family or friends, in case I lose them in the war. In case they die. That’s why I keep a certain distance from them,” says Omaia.

Wars don't end when bombs stop falling. Help us be there for children facing trauma. Visit nrc.no/donate.

The violent conflict has affected her so strongly that she has created her own survival mechanisms. Putting the nightmares into words, writing a diary and drawing are some of the techniques Omaia and the children learn in the Better Learning Programme.

"I don’t want any close relationships with my family or friends. In case they die. That’s why I keep a certain distance from them."

Omaia continues:

“Firstly, I talk to myself and I listen to music. Secondly, before I fall asleep, I give myself an hour where I lie still and dream of far-off places. I can go where I want in my imagination – maybe to a quiet little cabin. And thirdly, I write.”

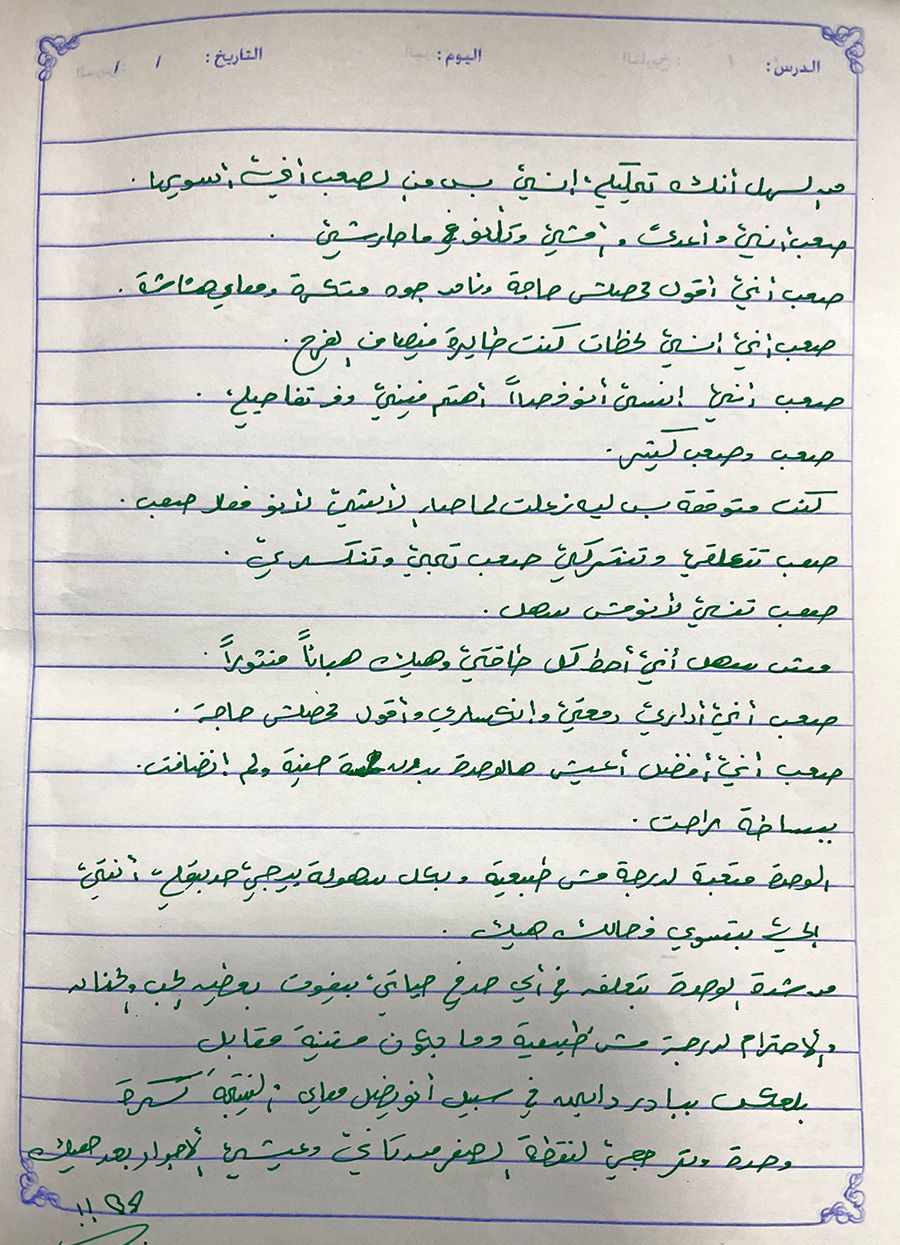

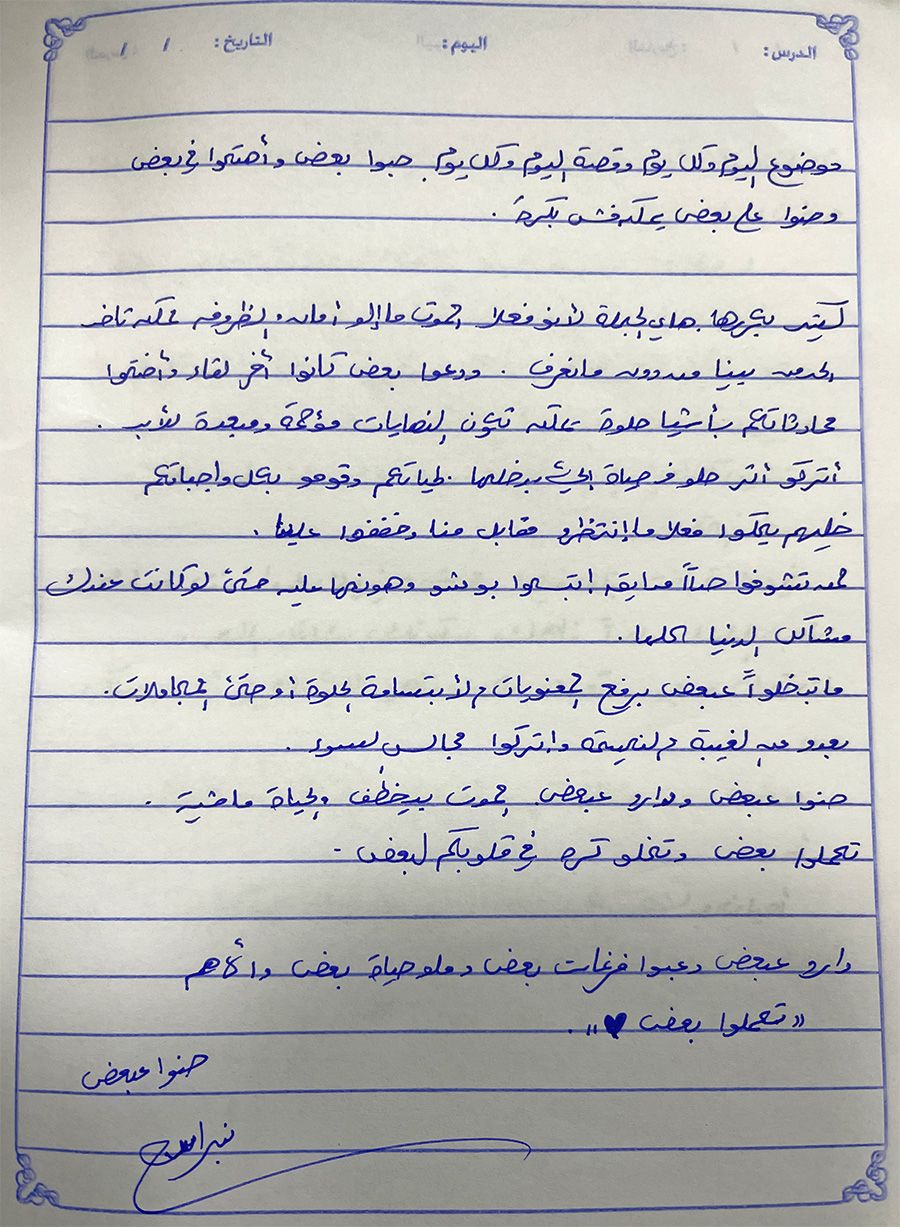

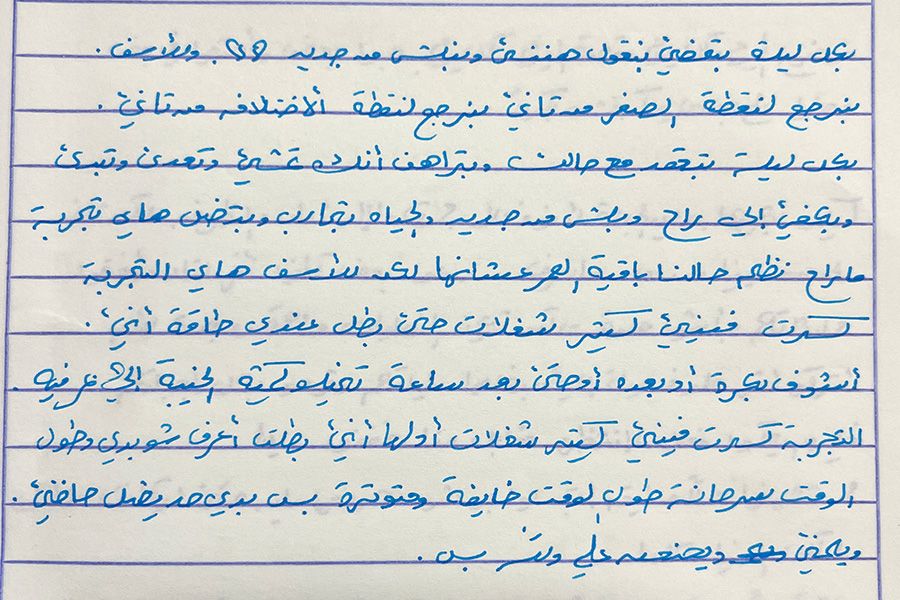

2022: Putting her nightmares into words, writing a diary and drawing are some of the techniques Omaia learned in elementary school through the Better Learning Programme.

“When I write, I call myself ‘Nebraz’,” she continues.

2022: Putting her nightmares into words, writing a diary and drawing are some of the techniques Omaia learned in elementary school through the Better Learning Programme.

2022: Putting her nightmares into words, writing a diary and drawing are some of the techniques Omaia learned in elementary school through the Better Learning Programme.

And just as Omaia says this, the power comes back on in the room. She brightens up:

“I’m not quite sure how it started, but I remember one day I started writing about my dreams and my feelings. I write when something happens in my life. Writing makes me less stressed. I’ve been doing it for three years.”

“There was a woman at school who advised me to keep writing. She gave me a notebook and said I should write every day, and save the book. But I don’t save my notebooks. I burn them. I burn them once a year.”

Why do you burn them?

“I just don’t want them.”

Professor Jon-Håkon Schultz of the University of Tromsø in Norway. Photo: NRC

Professor Jon-Håkon Schultz of the University of Tromsø in Norway. Photo: NRC

2017: Teacher Rania has been trained by NRC in how to support children experiencing stress, trauma and nightmares. Here she shows her students how to do relaxation exercises.

2017: Teacher Rania has been trained by NRC in how to support children experiencing stress, trauma and nightmares. Here she shows her students how to do relaxation exercises.

2017: Omaia talks about her feelings with her teacher Etemad.

2017: Omaia talks about her feelings with her teacher Etemad.

Better Learning Programme (BLP)

* The Better Learning Programme (BLP) is currently in use in schools in 26 of NRC’s programme countries. It was jointly developed by NRC and Jon-Håkon Schultz, a professor of educational psychology at UiT The Arctic University of Norway in Tromsø.

* This year marks ten years since NRC introduced Better Learning as part of our relief work. It was first launched in Palestine in 2012.

* Better Learning is a classroom-based psychosocial approach to supporting children who have been exposed to traumatic experiences as a result of conflict and displacement. The programme creates the right conditions to improve children’s ability to learn. It mobilises children’s support networks of caregivers, teachers and school counsellors – and takes a broad approach to helping to restore a sense of normality and hope.

* Better Learning can be used by any teacher or school counsellor who has received training. This makes the programme ideal in emergency situations and in places where resources are lacking and there are other challenges.

Read more about the Better Learning Programme and the teachers who use it

* Since 2012, as many as 67 per cent of Palestinian children have reported that they have stopped having trauma-related nightmares thanks to Better Learning.

* Some 79 per cent of Palestinian children reported improvements in their ability to do homework after participating in Better Learning.

Source.

Professor Jon-Håkon Schultz of the University of Tromsø in Norway. Photo: NRC

2017: Teacher Rania has been trained by NRC in how to support children experiencing stress, trauma and nightmares. Here she shows her students how to do relaxation exercises.

Terrible memories

Gaza City in 2017: “What's wrong?” asks 13-year-old Omaia’s teacher, Etemad, taking the young girl’s hand. Then the girl in school uniform starts crying. She says she’s scared. And that she has nightmares.

2017: Omaia talks about her feelings with her teacher Etemad.

The nightmares are the frightening memories from her experiences in 2014.

“I saw women and girls fleeing without clothes on, trying their best to cover themselves. They ran with their children. Others were carrying the few belongings they had managed to bring with them from home as they fled. My father was with me. I remember carrying a bag. As if I was on my way to a picnic. There were loud noises all around us. People were screaming and crying. But I ... I just looked at people normally. I looked at them the way I usually do. When we came to a dead end, I started crying. Because when we came to the end of that street, we saw body parts and blood.”

Post-traumatic nightmares

“Close your eyes,” says Etemad, and 13-year-old Omaia does as she’s told.

Etemad is a teacher with special expertise in the Better Learning Programme. She helps children who are struggling with stress and the trauma of war.

Now she says to Omaia: “Breathe. Breathe slowly: In. Out. In. Out … And now: imagine a place where it’s nice to be.” And Omaia imagines herself in a small cabin. Outside the cabin, everything is green and there are butterflies in the air. She is sitting alone in the cabin. She feels safe even though she is alone.

This is how Omaia finds peace.

2017: Omaia breaks down in tears.

Wars don't end when bombs stop falling. Help us be there for children facing trauma. Visit nrc.no/donate.

Today – in 2022 – Omaia is in her final year of lower secondary school. She will soon be starting upper secondary school. Later, she wants to study to become a psychologist. She plans to open a centre where she can help people who are struggling with mental illness.

She’s still quite young, but she doesn’t have the wandering gaze you would expect from someone her age. It is as if Omaia, despite her short life, has developed a seriousness – a certain weightiness – which usually comes only after a long life.

2022: Today she is in her final year of lower secondary school. She will soon start upper secondary, and wants to study to become a psychologist.

“In 2014, I was a child, but I was not afraid. Now that I’ve grown up, I’m scared,” she says.

When did you start having nightmares?

“About a month after the bombings in 2014. I remember the first time I heard about Better Learning. They said at school that we could apply to join a programme that could help children. They gave me a form to fill out. There were questions about what my nightmares were like and things like that. And then I was accepted to the programme. I participated in six group discussions and six one-on-one conversations with the BLP teacher. We talked about our nightmares and our feelings.”

Did it help you?

“Yes, it helped me relax more. I was less scared. It gave me the opportunity to tell how I really felt. And the nightmares stopped after about three years. I still use the exercises today. I breathe in and out when I’m angry or nervous.”

The bloody summer

July and August 2014. It was the bloody summer when Gaza was attacked by Israel from the air and the sea, after rockets were fired on Israel from Gaza. When entire neighbourhoods were flattened, and tens of thousands of people were left with nothing but destroyed homes.

When Israeli ground forces were sent into Gaza on 18 July, and withdrawn following a ceasefire on 5 August, with an open-ended agreement announced three weeks later. When families lost their children. When more than 2,000 Palestinians and 67 Israelis were killed and about 10,000 people were injured.

When Omaia was 13 years old, she sang for her school. You can see the video here:

2017: Omaia breaks down in tears.

2017: Omaia breaks down in tears.

2022: Today she is in her final year of lower secondary school. She will soon start upper secondary, and wants to study to become a psychologist.

2022: Today she is in her final year of lower secondary school. She will soon start upper secondary, and wants to study to become a psychologist.

Nervous and afraid

“I don’t know what happened, but when the bombing was most intense in 2021, we were all together, and we were close to each other. Some began to recite the creed, while others asked one another for forgiveness. My uncle came into the room and asked us to forgive each other. Suddenly, my grandfather came and started singing… and in the middle of all this, I was afraid.

“I cried for 11 days.”

She reads from her notebook:

“Every night, we say that tomorrow is a new day. But unfortunately, we just start at zero again … Every night, you are alone and make a bet with yourself that you will not start at zero again … Life is full of experiences. And this is just one of them. But don’t judge yourself. You have a long life ahead of you …”

“Unfortunately, this experience has ruined a lot of things in me. So much so, that I have lost all my energy … I’ll see you tomorrow, the next day and the next hour … But I always have this feeling of disappointment inside me … most of the time I am scared and afraid.”

2022: “But don’t judge yourself. You have a long life ahead of you…”, Omaia writes in her diary.

2022: “But don’t judge yourself. You have a long life ahead of you…”, Omaia writes in her diary.

Omaia smiles.

She closes her notebook.

And then recites a final sentence:

“I just want someone to hold me.”