Between a shock

and a hard place

How BRCiS builds resilience in Somalia despite unprecedented challenges

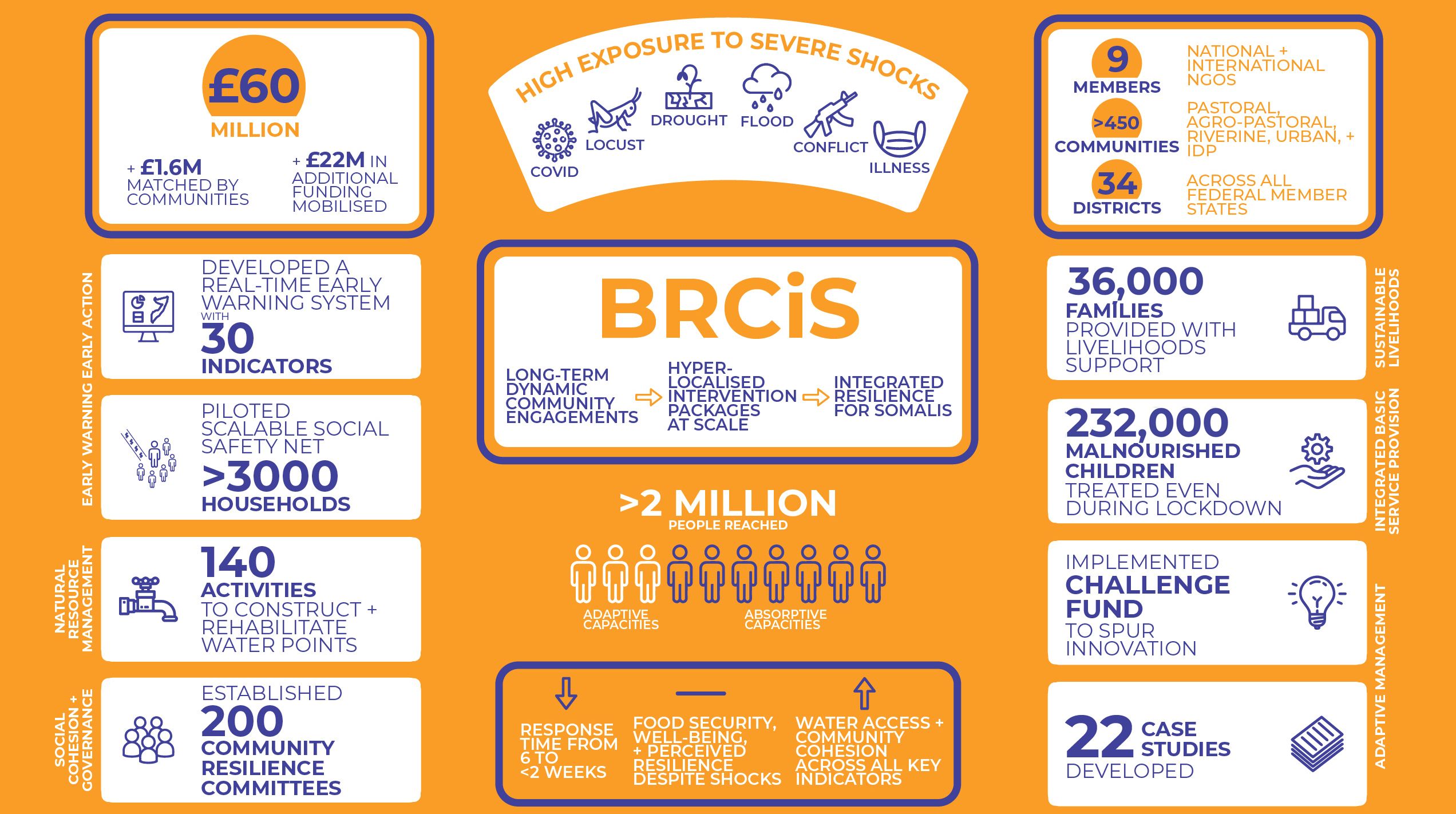

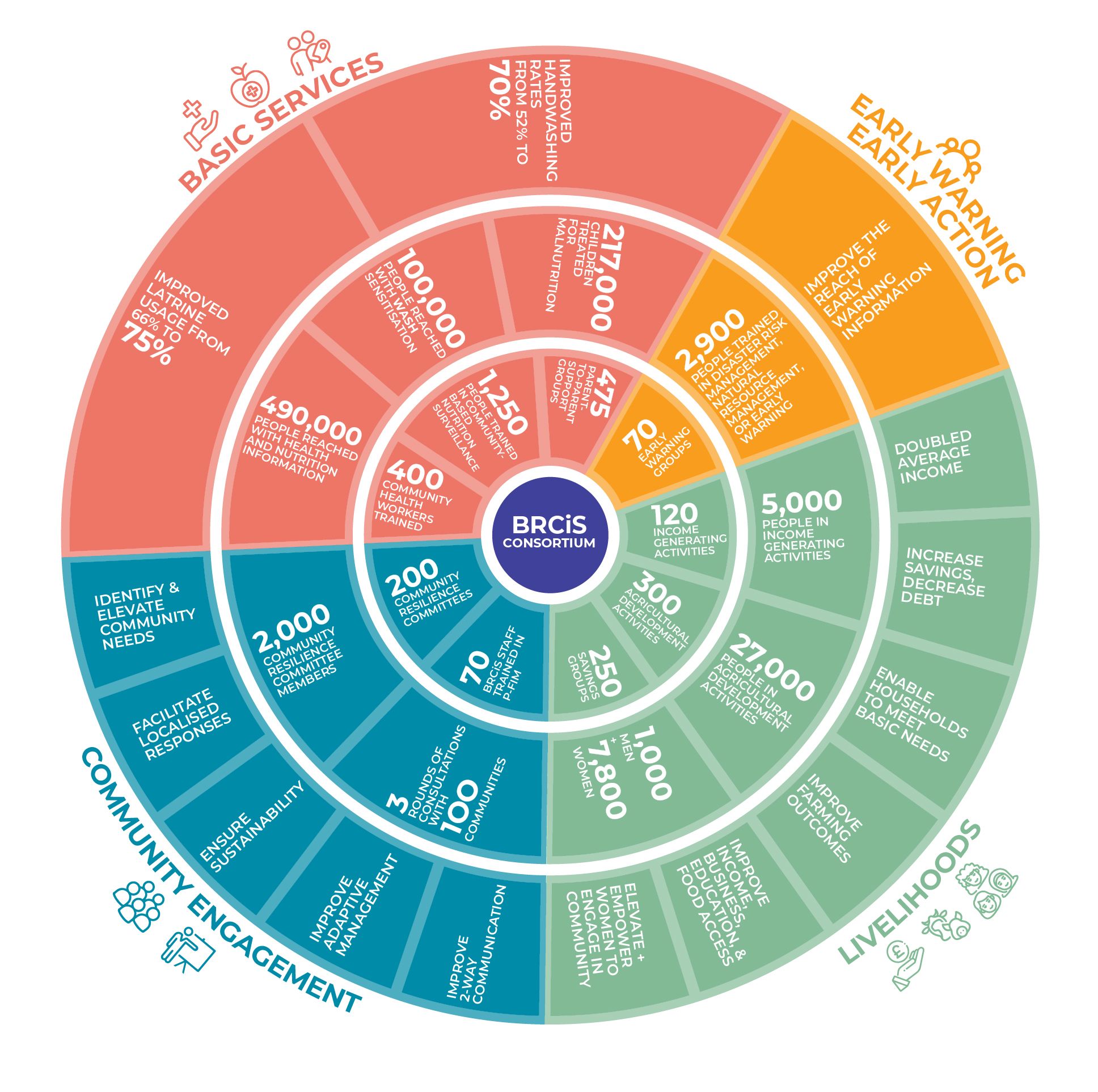

Key achievements

In 2017, communities in Somalia faced their fourth failed rainy season in a row and the worst food security situation since 2011’s lethal famine. When rains came in 2018, they brought hope for respite, recovery, a chance for families and communities to rebuild what was lost.

At the close of BRCiS 1 and heading into BRCiS 2, government, civil society, and communities were optimistic that, with such a major shock behind them, the next four years could be focused on the future. This would enable them to regain stability, expand their livelihoods, improve integrated basic services, and build a supportive environment to enable longer term resilience.

Unfortunately, Somalia, the Horn of Africa, and the world would face a very different reality.

Since the 2016/17 drought, Somalia and its communities have been hit again, again, and again.

In addition to direct impacts on health, income, infrastructure, crops, and food security, these crises have interacted, compounded, and created knock-on effects, affecting all facets of Somalis’ lives.

As a result, BRCiS and its communities have had to adapt, adapt, adapt.

This is the story, illustrated with data, video and photography, of how the UK government-funded BRCiS 2 project, the BRCiS Consortium and participant communities found their way to strengthen resilience capacities in this context of hardships and disasters.

It is designed to be interactive, so you can hover and click on the buttons and graphs to explore and learn more. The data used comes from BRCiS' internal monitoring and evaluation systems and third party monitors.

We acknowledge that not all impact can be directly attributed to the BRCiS 2 project interventions, as resilience and humanitarian projects are only one factor affecting individual, household and community experiences. At the same time, the data and our experiences that this report shares have demonstrated the value of these investments.

Stabilising communities in a volatile context

Early Warning Early Action

Preventing displacement

In April 2022, 50 drought-impacted rural villages hosted an average of 70 households each, and as many as 230.

On average, only 20 households left.

Real-time risk monitoring

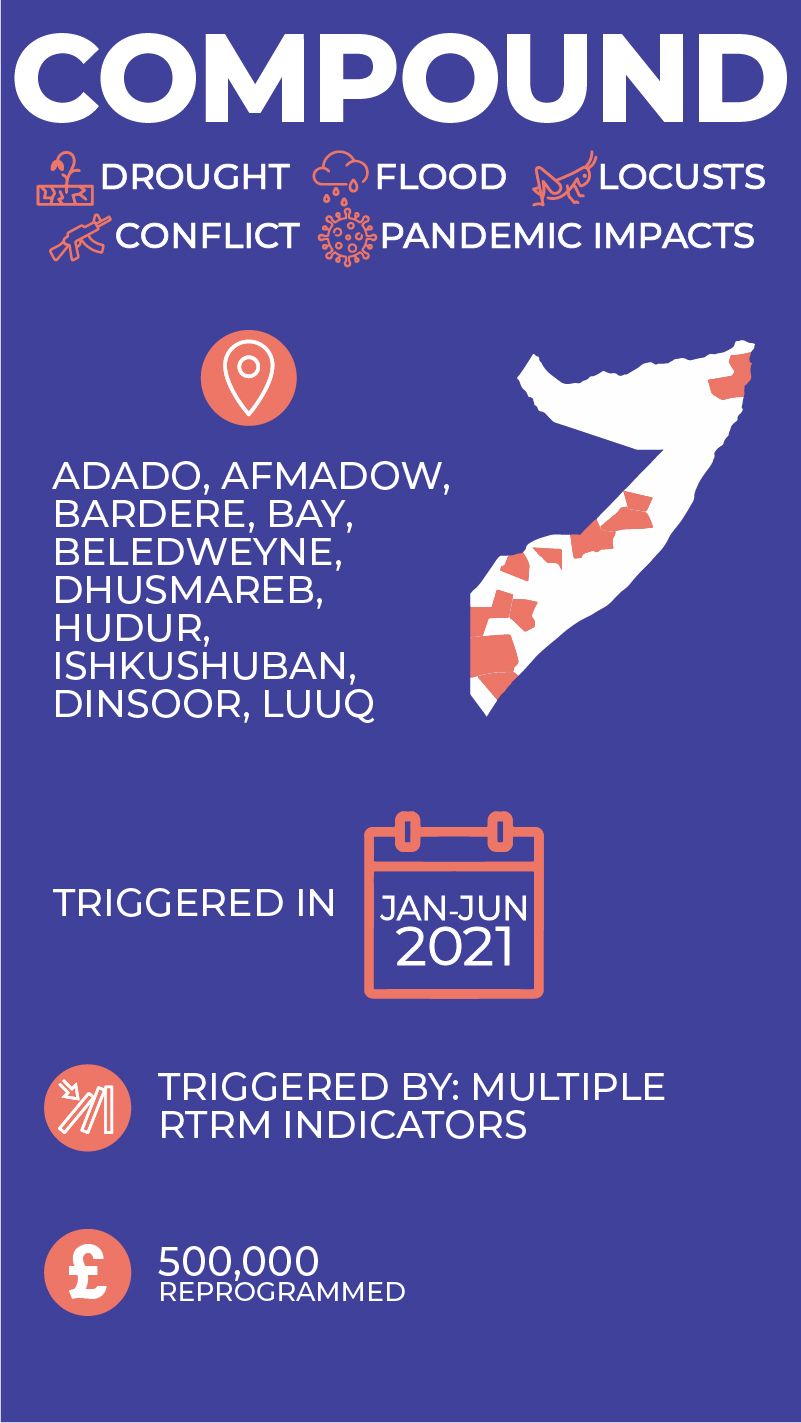

Some shocks, like the Covid-19 pandemic, were widespread, while others were intense but geographically concentrated. While Somalia has a robust national early warning framework, BRCiS 2 built up community-level monitoring systems to provide access to real-time, hyper-localised early warning data via its Real-Time Risk Monitoring (RTRM) System. This enabled extraordinarily cost-effective, targeted responses.

Unlike many early warning systems, the RTRM system triggers in response to both individual shocks and consecutive, overlapping, or compound shocks. This is crucial in a context like Somalia, where rapid and slow-onset shocks as well as the cumulative effects of many smaller, even unrelated shocks, can spell disaster.

Early actions and early responses

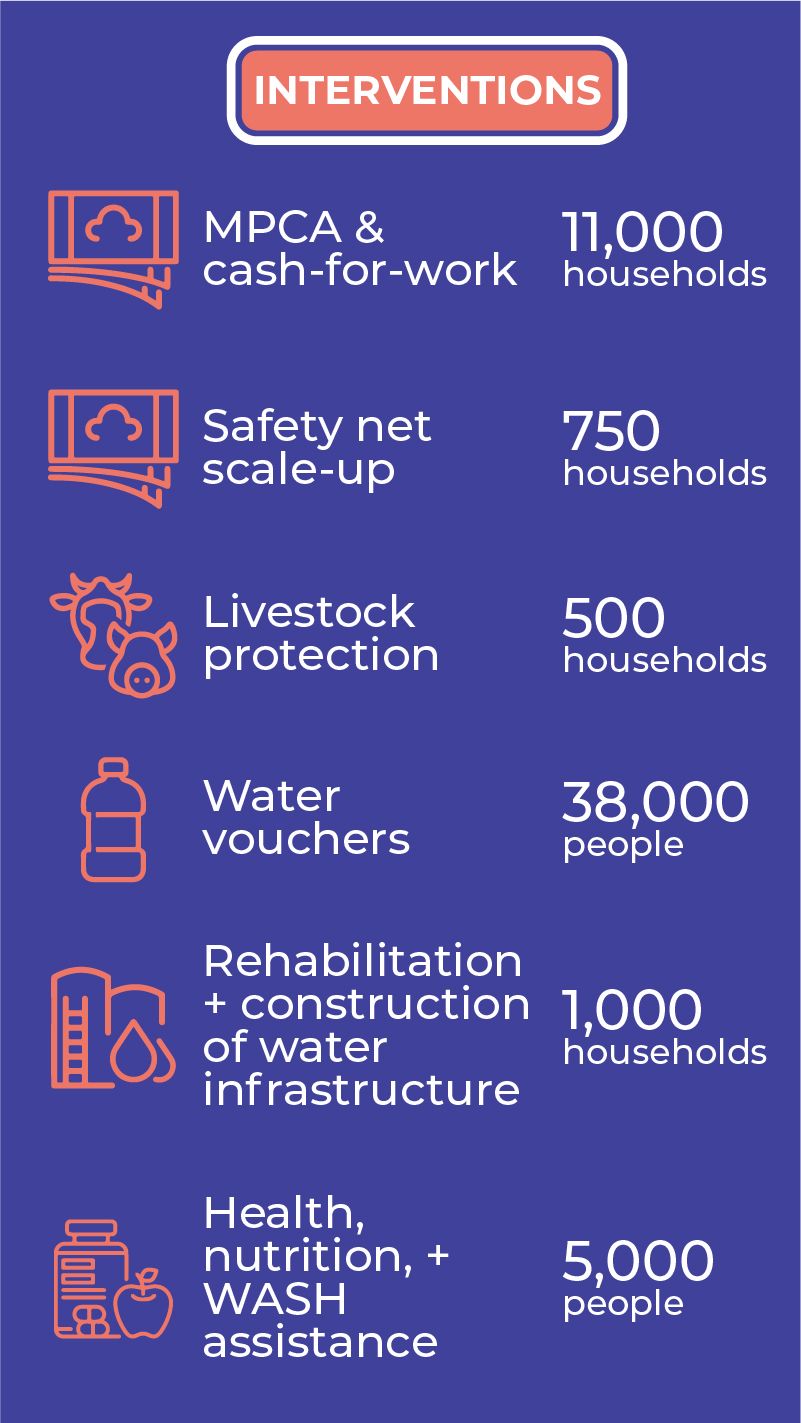

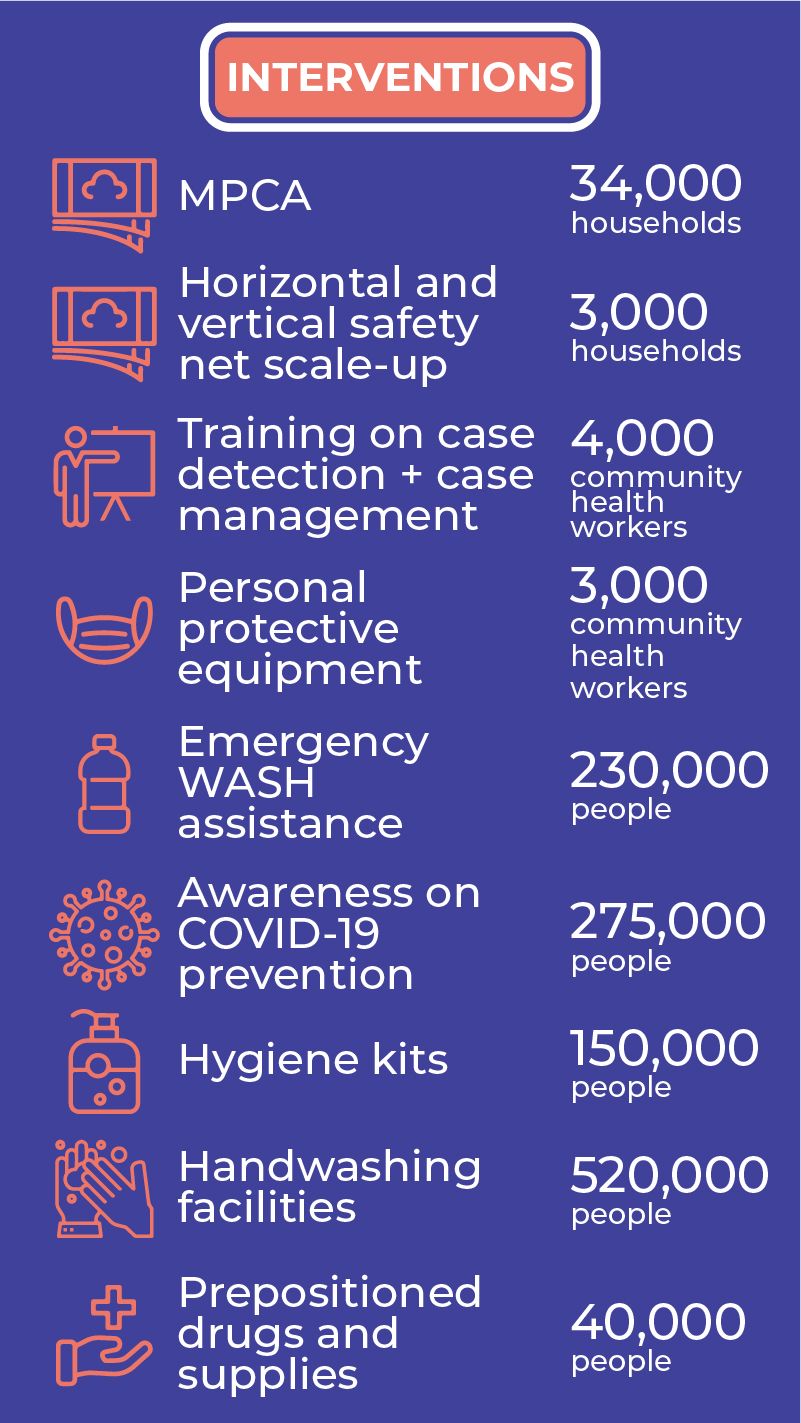

When the RTRM system is triggered, BRCiS responds with a tailored package of early interventions. This almost always includes multi-purpose cash assistance and often includes water vouchers, health and hygiene kits, mosquito nets, agricultural inputs, or fodder for animals.

"When I received the transfer, I felt so much excitement. I was able to repay my debt and buy food and other essentials.”

As part of its Early Warning Early Action framework, BRCiS 2 piloted a scalable social safety net that provided chronically vulnerable households with regular, predictable, and reliable cash transfers of $20 per month for two years, plus an additional $20 per month for three to six months during emergencies.

“I am grateful for the continuous support I have received for the past seven months. It has impacted my life positively. I have been able to feed my children regularly. Over the last three months I have been able to save to pay my children’s school fees. I am now hoping to expand my grocery business.”

Crisis Modifier

When the RTRM system raises red flags, Consortium Members can repurpose a component of existing budgets to meet urgent needs immediately. To address larger shocks, they generally mobilise additional financing.

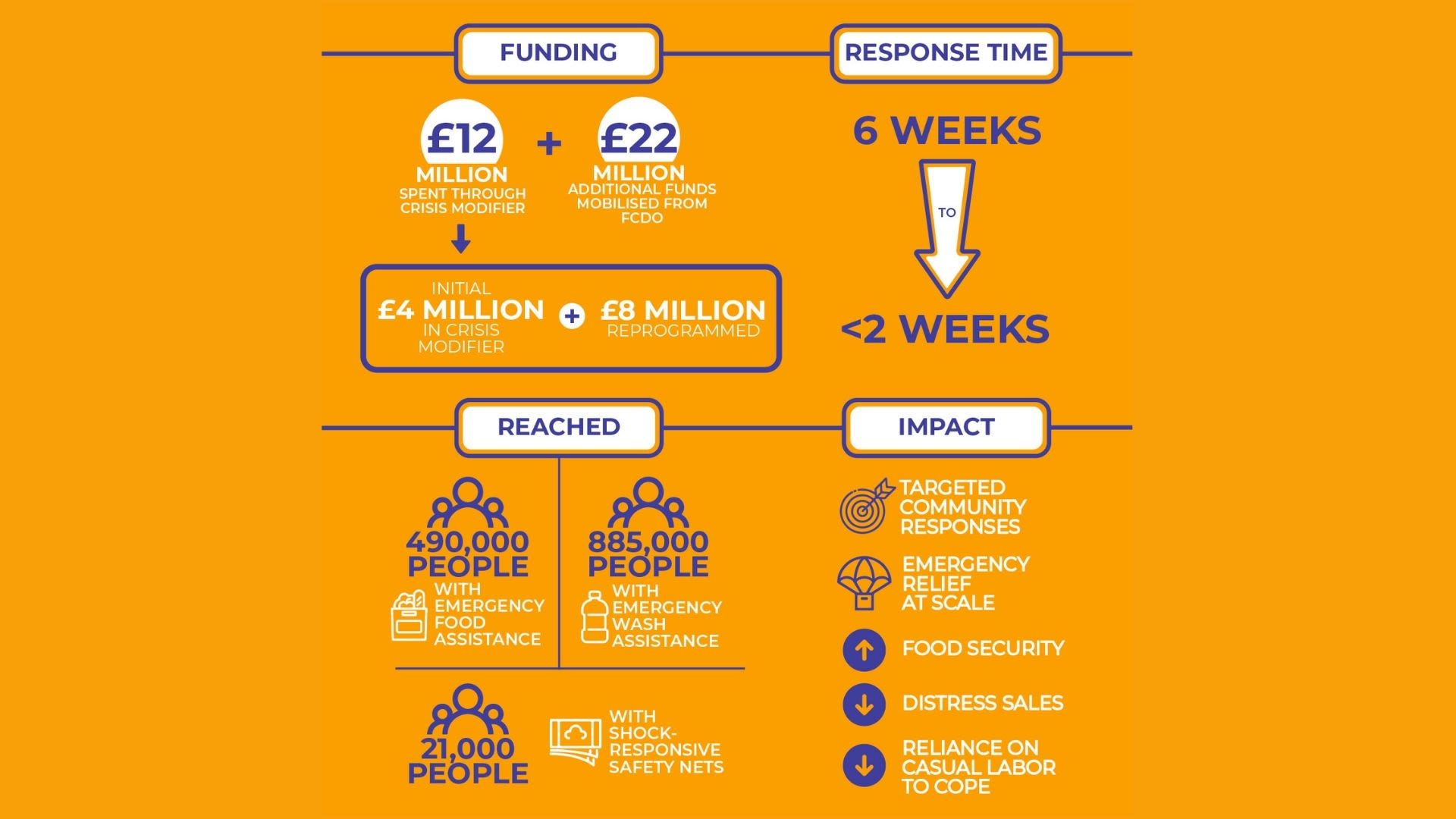

Based on learnings from BRCiS 1 and the high risk of shocks in Somalia, the initial BRCiS 2 budget set aside £4 million as a contingency fund, or Crisis Modifier. This fund was designed for early action, to stabilise local situations after community and BRCiS Members' response capacities were exhausted.

While an important step, the shocks experienced during BRCiS 2 were so frequent, diverse, and intense that almost the entire £4 million was spent on addressing the first shock alone.

Rapid, localised support

Examples of BRCiS' responses

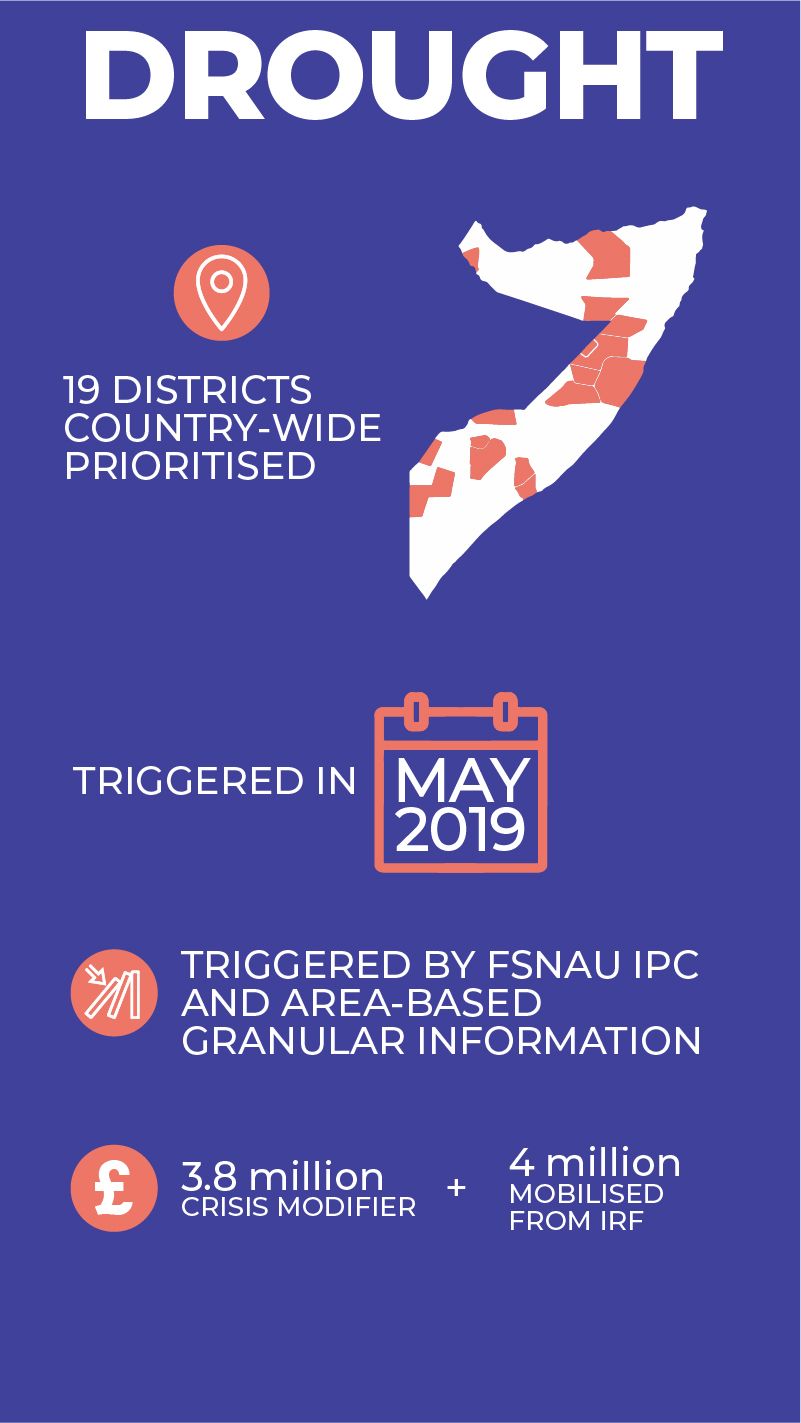

Just as communities were starting to recover from the 2017 drought, the 2018 deyr rains failed. Struggling communities suddenly faced drought conditions resulting in crisis and emergency-level food insecurity – again.

For BRCiS, early action means anticipating and mitigating the impacts of shocks as quickly as possible. So when the 2019 gu rainy season was also late – and one of the driest on record – BRCiS activated the Crisis Modifier.

Triggered on May 20, 2019, the response in prioritised areas began in June, significantly faster than possible if relying exclusively on traditional humanitarian financing channels. The disaster was so severe that almost the entire £4 million of the contingency fund was used.

An additional £4 million in Internal Risk Facility funding from the UK government enabled BRCiS to continue the response in prioritised districts and expand the response to other communities in need across the country.

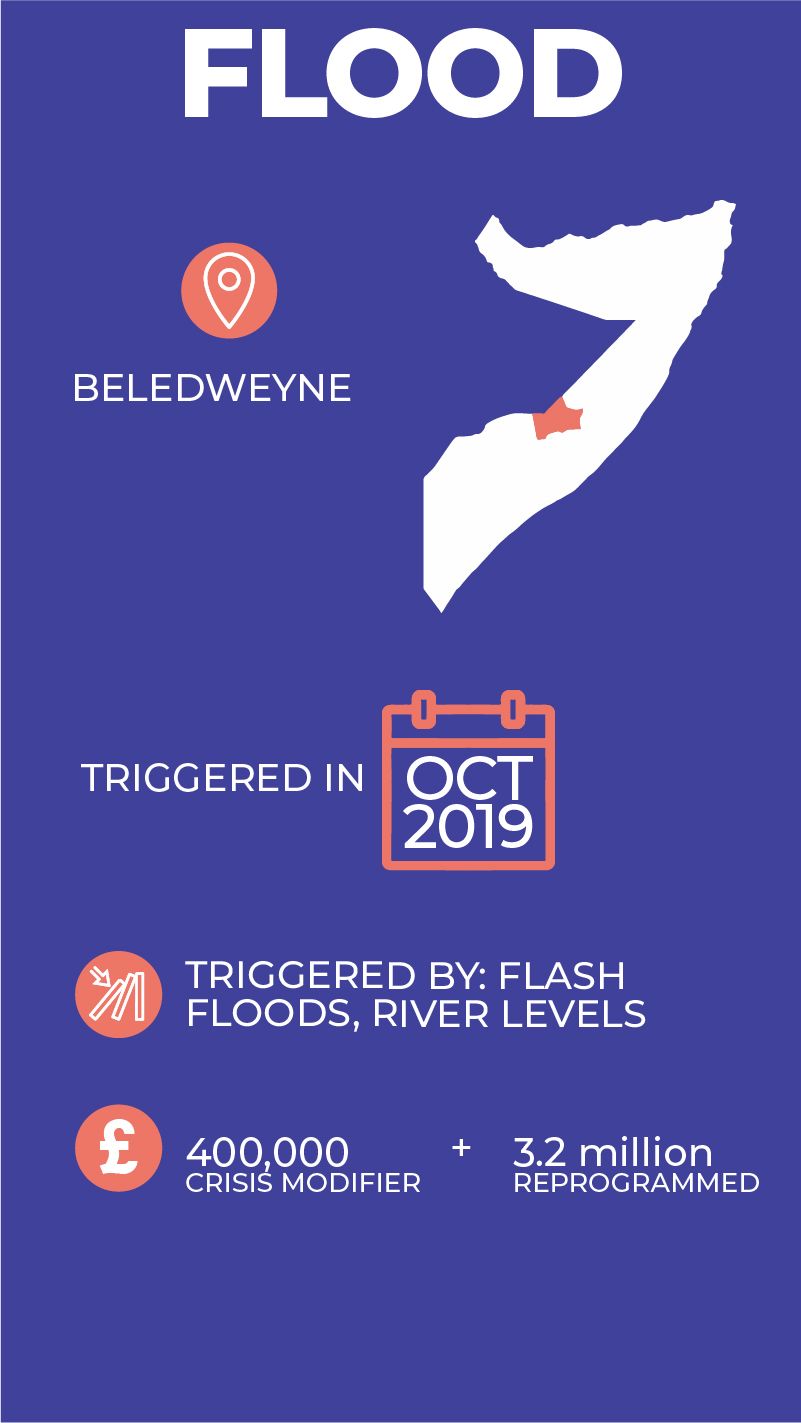

Seasonal flooding is fairly normal in certain parts of Somalia, but 2019's deyr season flooding was the worst seen in recent history, impacting over half a million and displacing 370,000 people across southern and central Somalia (OCHA).

Beledweyne, where BRCiS communities line the banks of the Shabelle River, was hit hardest. Flooding impacted the main town, submerged surrounding villages, and trapped people in their homes. It wiped out farms, infrastructure, and roads and led to broader health, water, and food security issues.

Thanks to accurate early warning information on rainfall and upstream river levels, BRCiS Members were able to predict the flooding, activate the Crisis Modifier, and initiate early action ahead of the shock. As a result, Members, the Beledweyne Flood Task Force, and local Community Resilience Committees (CRCs) were able to plan the evacuation and response before the shock even struck. They were also able to rapidly finance and implement the response – within just a few days of displacement – and enable the community to return to their homes as soon as river levels receded. Once the shock was over, the adaptable nature of the BRCiS Community Action Plans enabled the CRCs to prioritise irrigation infrastructure repairs in order to help the local population fully recover.

Somalia's first confirmed case of COVID-19 was reported on March 16, 2020 in Mogadishu. Beyond its direct health impact, the virus multiplied the effects of the existing complex humanitarian crisis on both BRCiS communities and the Consortium itself.

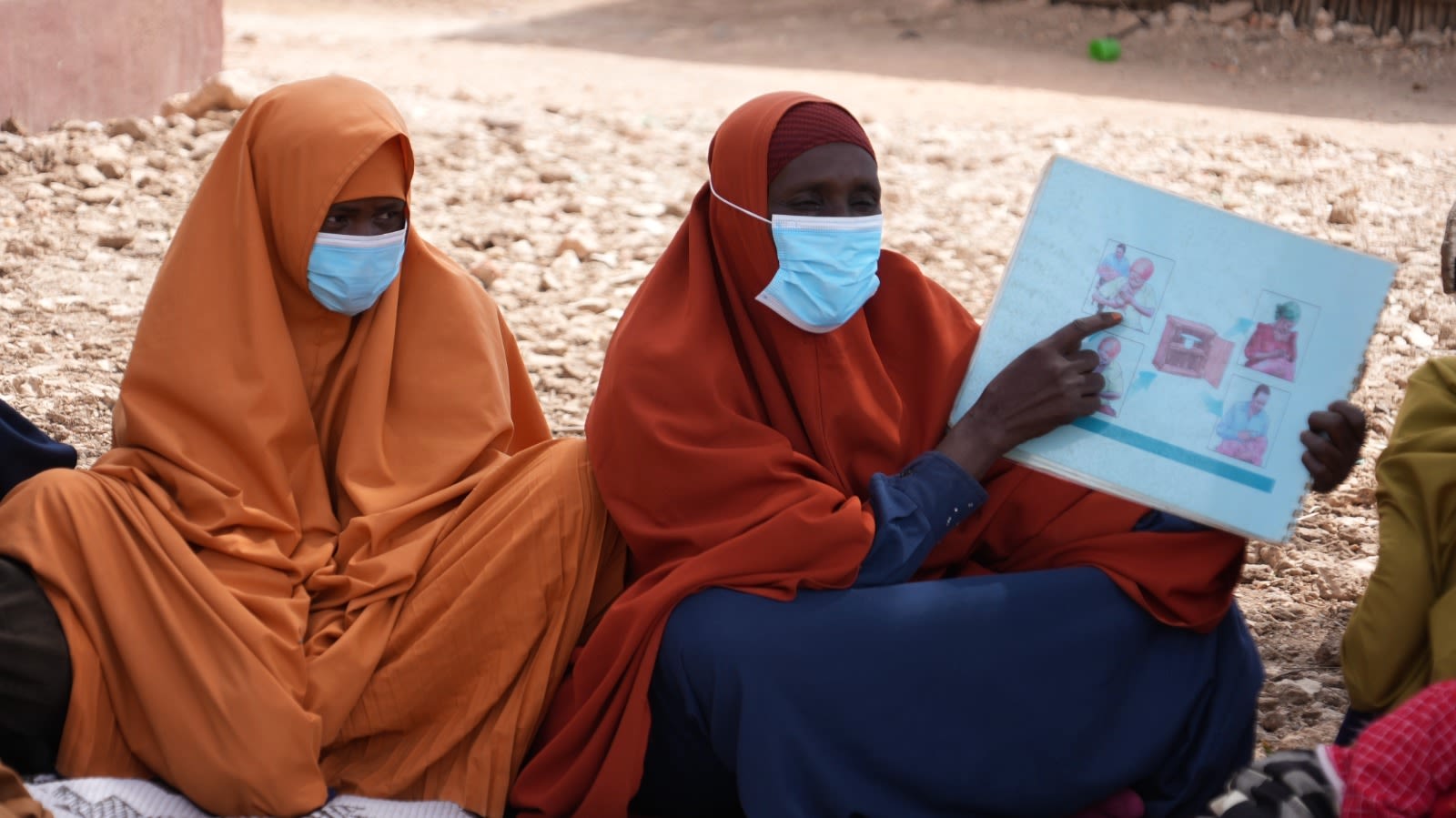

Because BRCiS already had a network of Community Health Workers, Members were able to begin sensitisation on COVID-19 prevention within participant communities within just 4 weeks – parallel to the development of official training documents. BRCiS’ guidance around COVID-19-safe implementation and adaptation followed a do-no-harm philosophy and systematically engaged communities through dialogues and local influencers.

“Without the cash support, most households would inevitably have starved.”

What started as a participation revolution became an empowerment revolution, as local groups implemented activities nearly independently.

Ultimately, the health consequences of the pandemic fell short of worst-case scenarios, but the economic impacts were widespread and severe.

The virus is serious, but survival is much more challenging.

Adapting safety net systems for pandemic (and nutritional) monitoring

In the absence of testing and pandemic monitoring in rural areas and among hard-to-reach and traditionally under-served populations, BRCiS rapidly adapted and mobilised the safety net’s monitoring system to track the spread of the virus, access to critical preventative supplies, and uptake of preventative behaviours.

The Consortium’s learning partner, Evidence for Change (E4C), estimated COVID-19 case and death rates using the Verbal Autopsy methodology and COVID-19 Rapid Mortality Surveillance (CRMS) software developed by WHO and its partners. The results suggested that COVID-19 case rates among BRCiS safety net participants were around 75 times higher than the lab-confirmed rates across the country, as reported by WHO. These findings confirmed a known equity issue common in official pandemic statistics and health data:

The most vulnerable are largely, and systematically, under-represented.

Community consultations throughout 2020 revealed an unfortunate truth – between the COVID-19 pandemic, economic and political instability, surge in armed conflict, locust infestations, and recurrent flooding and drought – communities were overwhelmed. For the first time, monitoring showed that MPCA recipients were still unable to meet their basic food needs even after three months of support.

This collection of shocks triggered the Crisis Modifier in January/February 2021 and again in June, but by this point, BRCiS and other humanitarian organizations’ budgets had worn thin. While the Consortium managed to respond, prioritization was harsh, and local field teams were unable to support many of the households and communities who desperately needed help.

Lessons learned

By the end of 2021, BRCiS had demonstrated the value of its EWEA investments in addressing a range of shocks in a timely way.

The current drought's extent and severity are truly testing BRCiS' approach, as the ghosts of the famines of the 80s and of 2011 stare the country down.

- November 23, 2021: The Federal Government of Somalia declares a state of emergency and appeals for humanitarian assistance.

- December 17: 3.2 million people affected nationwide and 169,000 people displaced.

- January 2022: 1.4 million children malnourished.

- February: 4.3 million people affected and 271,000 displaced.

- January to March: BRCiS used £1.7 million from its savings and mobilised £5 million from the IRF and £1.4 million additional USAID funding to mitigate the impact of the drought.

- April: 745,000 people displaced. BRCiS mobilised £6.1 million in IRF funding, including £ 1.1 million from the Qatari Fund for Development (QFfD).

As BRCiS 2 closes out, BRCiS Members, the Somali Government, and fellow humanitarians are scrambling – again – to avert a famine that threatens not only to destroy their hard work over the past eight years, but to take the livelihoods, hopes, and lives of people across Somalia.

Drought resilience =

Sustainable water systems

Ensuring sustained access to water

BRCiS installed 127 pieces of water infrastructure.

Even after three failed rainy seasons, 84% remain operational.

While BRCiS has an important emphasis on crisis modification, its mandate is to build resilience to drought. Since clean water is the essential resource in Somalia – sustaining human lives, enabling farming, supporting livestock for food and livelihoods, maintaining the safety of women and children, and preventing malnutrition and disease – improving water access and systems were primary objectives of BRCiS 2.

By the end of December 2021, BRCiS had carried out 165 activities to construct or rehabilitate irrigation systems and water infrastructure.

By the end of March 2022, it had reached over 300,000 people with water for productive uses and over 2 million people with sustained access to safe water year-round.

“If you haven’t solved access to water, you’ve done little.

Yes, individual and community capacities to understand and anticipate shocks are helpful. Yes, mothers and fathers who understand malnutrition are better off in a drought, but if they don't have clean water, what will they be able to do?

If you have water, you can have food, you can have milk, and your children can survive.”

Most communities were able to successfully withstand the first failed rainy season in 2021, relying on water resources saved from previous rains, sometimes in the earth dams and other catchments built through the project. However, as the current drought has worn on and large surface catchments and other water sources have increasingly dried up, more and more people are abandoning their homes and livelihoods in search of food, water, and basic services.

The majority of these IDPs – two in every three families – are rural residents moving to urban centres in search of food and basic needs. Unfortunately, as bad as the drought conditions are, a recent NRC study found that the outlook for people who are moving to IDP camps is only slightly better than in their villages.

This was confirmed by BRCiS monitoring data, collected after the first distribution of MPCAs to 21,700 households in early 2022.

BRCiS-drilled boreholes in rural areas have not only been a lifeline, they have helped to reduce drought-induced, rural-urban displacement and are serving larger and larger catchment areas – including refugees and IDPs from as far as Ethiopia.

“I would have sold my remaining livestock and joined the millions in the IDP camps, had I not found this borehole at Laanle. I have lived as a pastoralist my entire life, so it would have been difficult to start a new life in an urban setting. With this borehole, my prayers have been answered.”

At the end of BRCiS 2, the situation in Somalia is desperate. Still, communities where BRCiS’ investments were focused are holding out, cooperating and helping each other, advocating with the Consortium for assistance, and making use of all the resources they have to cope with the drought.

“Mine was one of the families who fled the village during the severe drought of 2016/17. This time, it is completely different. We now have constant water, and we don’t have to leave the village because of the drought.”

Communities are the heart of BRCiS

Building social capital & community cohesion

Boosting social capital

Before BRCiS 2, nearly a quarter of community members had no one to turn to for help and were unwilling to help others. Two years later, these numbers had declined by half.

Women’s voices and social capital also improved, reaching the same levels as men.

Establishing community structures

All BRCiS’ programming is carried out through community engagement and participation, allowing Consortium Members and communities to think beyond emergency response packages even as crises unfold. While transformation has been slow, it is always the goal.

True locally-led programming involves significant up-front investment in developing relationships and building trust through a multi-stage process.

Strengthening social capital

Over time, these structures help to build and strengthen social capital, community cohesion, and community ownership.

Horizontal connections with peers – including those from other genders, clans, and social groups – strengthen the fabric of the community and naturally reduce conflict.

Vertical connections with local authorities and other leaders amplify community members’ voices, giving many previously marginalised people and perspectives a seat at the decision-making table.

These structures – especially the CRCs – also support community ownership, ensuring sustainability of key infrastructure and activities and empowering communities to identify, prioritise – and in many cases meet – their own needs.

“Our community supports each other – the most vulnerable within the community and households that are displaced – as much as we can. However, the drought has significantly affected all of us – as well as our ability to support others.”

“The community supports those who are most vulnerable. In this period of drought, we are each contributing to provide water trucking to remote areas that have no access to water because of the drought.”

Community contributions

In total, BRCiS communities were so invested in the activities they prioritised that they collectively contributed over GBP 1.6 million worth of in-kind contributions, labour, land, and cash in the four years, even amid drought, COVID-19, and other shocks. This included:

- £191,400 contributed by an urban community in Erigavo to completely fund development of an artesian well by a private company to avert problems associated with recurrent drought.

- £117,000 in cash mobilised by CRCs and Disaster Committees in an urban community in Dhobley to support vulnerable households with unconditional cash transfers and non-food items.

- £GBP 69,000 raised by a rural community in Galkaayo – through remittances, sale of assets, and a loan – to completely fund the rehabilitation of a borehole.

- £61,000 contributed by a rural pastoral community in Dhusamareb to construct a livestock market.

- £46,000 raised by a rural community in Adado to fund 85% of the cost of a new borehole.

- Land valued at £38,000 contributed by an urban community in Hamarwen to a health facility.

Some community members had a perception that crowdfunding is always about contributing money to fund a project, yet there are many ways in which we can contribute towards a community project with the existing resources we have like land and labour.

Transformation takes time

New BRCiS communities tend to be primarily interested in humanitarian support. However, after about four years, as trust has been increasingly built, they see the value of, and are ready to engage in longer-term development, market-based, and systems-level interventions.

Because BRCiS’ funding cycle is longer than typical humanitarian financing and local leadership is empowered, communities can then engage in projects involving more risk. These include: communities co-funding infrastructure projects, securing group or individual loans from microfinance institutions, fundraising to support health facilities and manage water scarcity together, and engaging with the private sector on agriculture investments.

The preparatory work, which consists of stabilising income, supporting health and water services, and building social capital and leadership, creates a fertile ground for resilience to grow in the second half of an eight year cycle.

While much of BRCiS 2 was spent on early action and crisis modification, BRCiS’ long-lasting impact lives in the seeds of transformation it planted, in terms of building social capital and trust and generating early insights to inform future engagement in this area.

Community of collaboration & innovation

The BRCiS Consortium

None of these achievements would be possible without the local and international NGOs of the BRCiS Consortium.

Over the course of BRCiS 2, the nine Members have become a strong-knit community centred around open-minded collaboration and learning. This environment strengthens Members’ confidence in adopting new practices that have been tried and tested by others, resulting in more rapid uptake of recommendations from technical groups and accelerating change across a large group of organisations.

Looking ahead

Recommendations for

resilience-building

While BRCiS 2 successfully proved that the project’s model of integrated resilience works against moderate and compound shocks, the Consortium has no idea what will happen as the massive drought continues to unfold and the much-needed humanitarian scale up is not delivered.

Moving ahead, EWEA will remain central to the BRCiS approach, leveraging the gains from BRCiS 2 – including the RTRM and Crisis Modifier mechanisms – to channel emergency relief to drought-affected populations effectively. While the RTRM system currently collects data from a small group of villages within each district, the Consortium plans to work with communities to expand geographic coverage to collect a more representative sample of early warning data. It also aims to improve local involvement and ownership of the RTRM system and expand the use of the data collected to inform other early warning mechanisms.

The biggest lesson learned during BRCiS 2 is that sustainable water systems IS drought resilience. Since water is the centre of all aspects of Somali life, from food security to livelihoods to health and nutrition, the Consortium will situate water security at the centre of its programming, driving initial conversations with communities and linking all operational areas back to this key theme.

BRCiS derives its strength from its deep and meaningful relationships with local communities, and it will continue to invest in, empower, and work through community structures. To help build the resilience of the communities as a whole, BRCiS 3 will continue to apply replicable and sustainable approaches to stabilising the incomes of vulnerable groups.

While gaps in local health systems have long persisted, the COVID-19 pandemic – and BRCiS’ response – revealed the need to improve critical capacities in understanding, monitoring, and responding to health issues at both the family and community levels in order to facilitate decision-making in the face of future health shocks. BRCiS will continue to invest in behaviour change, demand creation, risk surveillance, and management capacities at both community and facility levels.

Despite its wide reach and meaningful impact, given the extensive needs across the country, BRCiS can only afford to do so much, and its teams often experience a lurking feeling that they aren’t working at the scale they need to be. To the extent possible given the emergency needs stemming from the drought, BRCiS hopes to continue to nurture the markets, private sector, and systems-level seeds it has planted, and to continue to build and strengthen relationships with local authorities, financial service providers, and other projects and actors, enabling the Consortium’s activities to have ever more sustainable and systematic impacts.

“They are many, the people who have left... they left because of a lack of water. This has happened in the past, in every drought...It used to happen before the project was implemented.

But now, people from other areas are moving here.”